CURIOSITY

Moments of tooth: Hamlet at the prosthodontist

The skull is uncompromising in its existential provocation. This is the bedrock, the final layer in one’s existence. And for an actor, it is both hugely symbolic and specific: it’s the perennial icon on ‘Hamlet’ posters.

It’s not the immediate sense of life spinning out in front of you in the way it might if you were involved in a car crash, but it’s a slow-burn realisation. One that allows for some distance between now and the Big Event – an objective distance for philosophising. I’m not so much an existentialist as an aspirant agnostic.

I would love the colour involved in being an absurdist (John Vlismas once commented that absurdism is like atheism with clowns!). But it’s just that I can’t claim to know enough either way to make any strong claims for meaning in the universe that hold me to one side of the fence.

Actually, it wasn’t the visit to the dentist that did it.

She was the beginning of a journey from the root canal to the maxillio-facial surgery on a molar (which splintered and threatened to crack my lower jaw) to the prosthodontist.

He is the guy who prepares a “prosthesis” in jaw restructuring and teeth implants. Let an actor know he is getting a prosthesis and he may have visions of Lawrence Olivier’s nose, or Antony Sher’s hunchback (for Richard III), Robert Downey Jnr’s armour for Ironman or Wickus’s transformation into a “prawn” in District 9: It’s showtime!

If you’ve never experienced Hamlet in performance, the skull appears in a scene between a gravedigger and Hamlet:

In Act 5, Scene 1, a scene filled with the gags of two clowns – Shakespeare knew how to fill the entire spectrum of absurdism (of human existence, perhaps) – and the sober meditations of a philosopher, Horatio.

To be exact, it is the final act that winds up the tragedy involving Hamlet’s own death. (Apologies for the spoiler if you haven’t experienced the play! But it has been a while since its premiere!) The skull given to Hamlet by the clownish gravedigger belongs to… another clown, Yorick.

There is a suggestion from academics that the references in the text may have related to a celebrity many actors and audience members would have known:

HAMLET: Alas! Poor Yorick, I knew him Horatio… Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table on a roar?

Those lines, spoken by the actor David Tenant in a 2008 Royal Shakespeare production of Hamlet, took on a new resonance when they were spoken to the skull of the pianist Andre Tchaikowski. (Unrelated to the Russian composer, he was born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer in Warsaw and smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto with the name Andrzej Czajkowski. Quite possibly he may even have met or passed by the protagonist of Polanski’s historical drama, The Pianist, Wladyslaw Szplilman, around that time.)

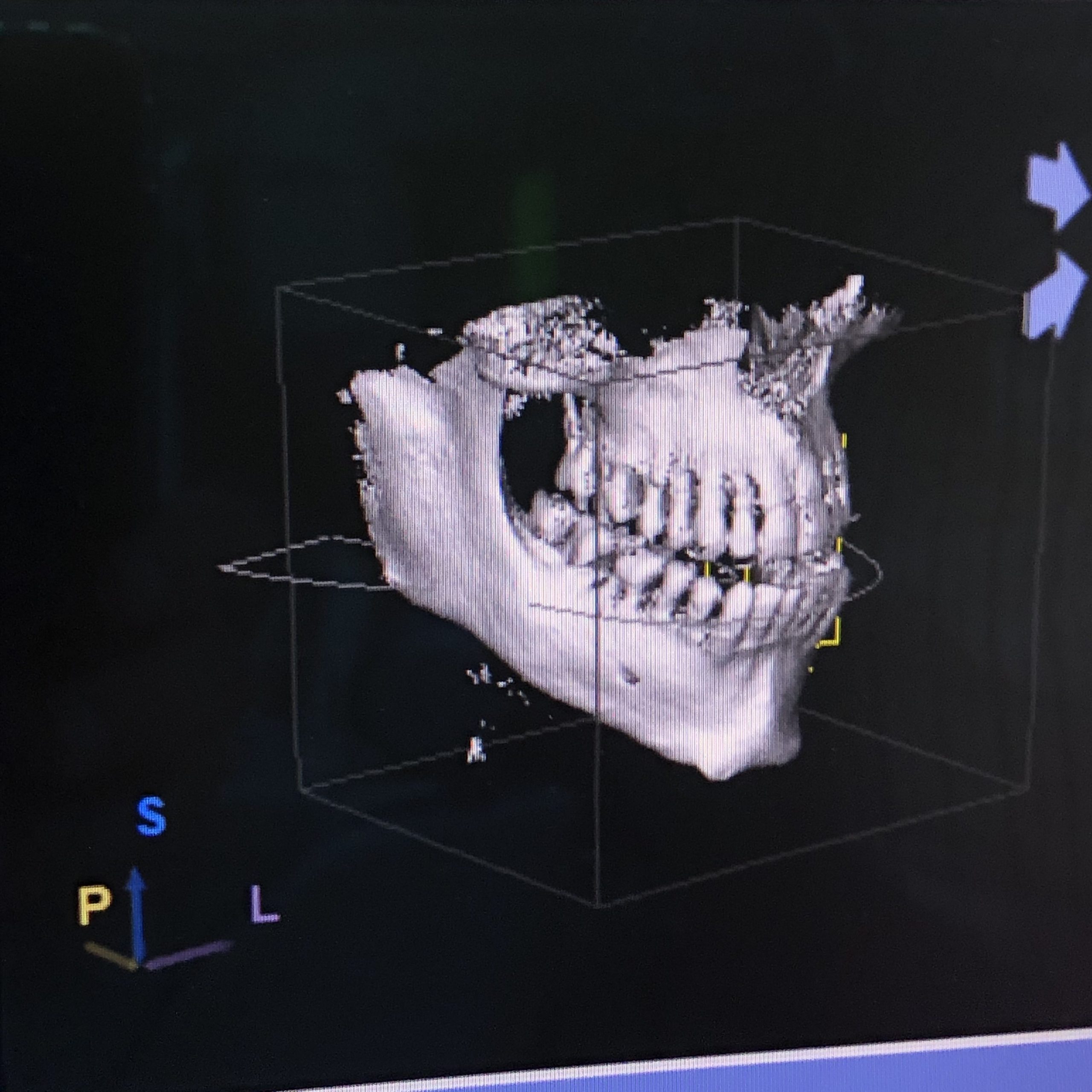

Tchaikowski had hoped that his skull would be used for the role of Yorick after his death, but it was not until Greg Doran’s production with Tenant that a director and cast plucked up the courage to use it. My own skull, post-prosthodontic scan, is projected onto a screen and made into a kind of 3D gamer’s hero, or CAD design item.

Prosthodontic scan (Image supplied by Ashley Dowds)

It’s the first time I’ve seen my face in its honest, bare-bones structure. It makes me think of Richard III, whose remains were discovered under the tarmac of a carpark in the city of Leicester, 527 years after he was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field.

Among the immortal lines spoken in Shakespeare’s plays, Richard III has one of the most memorable:

“A horse, a horse!” he screams as he is about to be obliterated by the new king, Henry VII, “my kingdom for a horse.”

A hundred years after that event, Shakespeare uses Richard’s rumoured deformity to create an arch-villain counterpoint to the coming king. For centuries, people had argued that this was really disingenuous character assassination on Shakespeare’s part, in favour of his own sovereign who would have blood ties to Henry VII.

The skeleton of King Richard III was discovered in 2012 beneath a car park, in the foundations of Greyfriars Church in Leicester, 500 years after he was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field. (Photo by Richard Pohle – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

The archaeological remains exhumed from under the car park though, bore out the rumours. The skeletal frame was scoliotic. (His teeth, judging by the perfectly preserved skull, are magnificent.) In fact, the find makes Richard III the poster boy for the University Of Leicester’s marketing strategy: “We led the search for Richard II. What could you discover… ?” The gravedigger’s response to Hamlet’s question about how long a skull might survive in the ground is out by hundreds, some say thousands of years:

HAMLET: How long will a man lie i’ the earth ere he rot? First Clown I’ faith, if he be not rotten before he die – as we have many pocky corses now-a-days, that will scarce hold the laying in – he will last you some eight year or nine year…

Imagine the First Clown’s surprise then if he had heard about Ötzi, the 5,300-year-old “iceman” whose body was found in 1991 by two German tourists on the Austrian-Italian border, near the Hauslabjoch pass. Granted, the iceman (named after the Ötztal Alps), had only recently surfaced from a glacier – quite different from soil. It was the isotope composition of the iceman’s teeth, along with pollen and dust grains, that narrowed his birthplace to Balzano in Northern Italy. His teeth offered the trace elements of mineral water from that area.

The narrative reconstruction of the last few moments before Ötzi’s demise are remarkable; Shakespearean, you could say! After an X-ray examination of the body, a flint arrowhead was found in Ötzi’s left shoulder, with a 2cm entry wound.

Doctors suggested that this would have severed the subclavian artery which meant he would have bled to death that early summer day, according to maple leaves and pollen found in his birch-bark containers. A deep cut to his right hand also suggested some hand-to-hand combat. What he was doing in the area, and why his assailants left behind his quiver and copper axe, is still a mystery though.

You can see a realistic-looking version of the iceman on the website of the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy. It was reconstructed using stereolithography of the skull and CT images by two “paleo artists” from the Netherlands. Thanks to them, we get to see what Ötzi, who was about 45 when he died, before even the pyramids or Stonehenge had been built.

My prosthodontist assures me that the scan of my jaw takes away the guesswork of an operation I may have to insert a tooth. It’s unlikely to happen, but if my remains were found under a car park in a few hundred years or emerging from a glacier in a few thousand, it would be interesting to hear the forensic narrative. Whatever it is, I hope there are clowns nearby! DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A superb blend of humour and science…artfully served !