Maverick Life: MUSIC

How to fail a Facebook challenge because you know too much – a lesson in SA musical history

Born in New York, a so-called ‘diplomat brat’, of the few aspects of South African culture that veteran writer Chris du Plessis could ever vividly recall was pennywhistler Spokes Mashiyane’s ‘King Kwela’ album and Miriam Makeba’s debut album in the US.

“With scant tangible proof of South Africa’s existence, these two albums were a security blanket of sorts” – Chris du Plessis

It’s one thing to wade through life doubting your own abilities. But it’s a whole new low to fail a Facebook challenge.

As is to be expected, a significant sector of life during lockdown is being played out on social media. And though I knew I would be called upon at some stage to participate in one of the exercises, it’s always a shock when it actually happens.

Thus, when requests were made by a journalist colleague (and respected music aficionado of long standing) and a trusted OFP (Old Friend from Pretoria), to select 10 record covers to post on on the platform with no explanation and so on and so forth, I felt both honoured and resentful.

Honoured, because I respect them as friends and colleagues and would have liked to please them. Resentful, because l’ve always experienced life as hard enough without any extra pressure to do anything you aren’t forced to do for basic survival.

I eventually decided on a transparently weak compromise: to ignore the original request and offer an explanation instead about some of my musical choices.

Not only as I found I would have really liked to know how others came to make their decisions but because I am a strong believer in free speech (even if you are specifically asked to shut the hell up) and allowing everyone to decide for themselves whether they wish to read things or not.

I also made the decision to not allocate someone to follow suit, as I found it all – after failing so miserably to comply with such a simple request obviously made to save people like me from themselves and the rest of the world – to be quite an exhausting experience. Herewith my first failed attempt to not include any info about my favourite album choices for anyone to not read if they do not wish to do so.

***

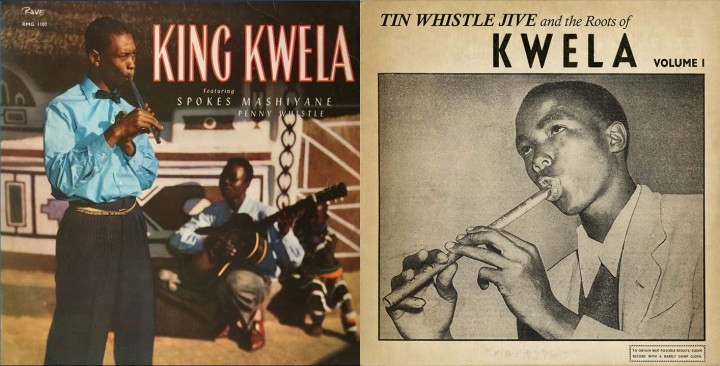

KING KWELA – Spokes Mashiyane

Although he was already one of South Africa’s most celebrated township musicians and one of the few to eventually be paid royalties by the record companies, Sponono “Spokes” Mashiyane’s aggressively marketed King Kwela compilation (on the shelves a year after my birth in 1958) propelled him into the South African music mainstream and afforded him a notable amount of international acclaim.

He was preceded by more competent Pennywhistle Jive players, (Kwela was a later term derived from police action against the players — see footnote below*).

Whistle-meisters such as Abia Themba, Ben Nkosi (one of the few, together with “Big Voice Jack” Lerole, Peter Makonotela of Elite Swingsters and Lemmy “Special’’ Mabaso, who could blow two different flageolets in separate keys simultaneously) and my personal favourite, Willard Cele – a disabled man from Alexandra township who made it hard to distinguish his tone and rapid fingering from the clarinet of Benny Goodman.

But Spokes introduced an ease and fluidity into a clever mesh of trans-Atlantic jazz, blues and township mixes never heard before.

At least half a century before all this, at the tail end of the 1800s, a 5.3 sq km area around Johannesburg’s Zoo Lake (formerly part of the original Braamfontein farm) was bought by one Hermann Ludwig Eckstein from Stuttgart, Germany, who was later to become president of the Chamber of Mines in Johannesburg and founder of the National Bank of the Republic of South Africa.

He named it Sachsenwald after Otto von Bismarck’s estate back in his homeland (wald = woods/forest).

Eckstein turned it into a timber plantation to service the burgeoning gold industry (hence the present-day names Forest Town and Saxonwold/Sachsenwald.)

Apparently of a slightly eccentric bent like his buddy Paul Kruger, he kept all sorts of animals on the zoological estate which was later stocked up further by one of his employees – an equally colourful character in SA history, Percy Fitzpatrick of Jock of the Bushveld fame – with a lion, a cheetah, a leopard, two giraffes, a hawk and four sable antelope.

A decade after Eckstein’s death at the turn of the previous century, his partners at Wehner Beit Co bequeathed some 200 acres of this land to the City of Johannesburg under the provision that it remains accessible to all people (read races) in Johannesburg. And it is for this reason that weekends saw a conglomeration of the polyglot South African society like never before at Eckstein Park (Zoo Lake).

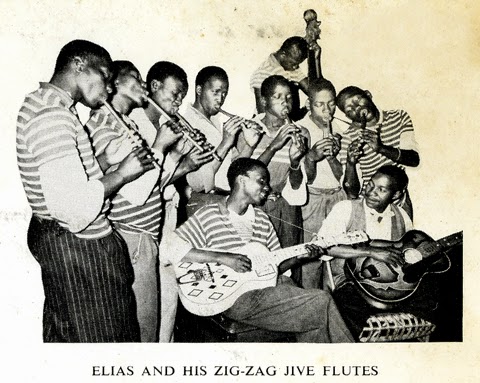

Sundays in particular were when all the young pennywhistlers (ages seven upwards) would band together (regularly comprising up to five whistlers and an acoustic guitar with names such as The Zig-Zag Jive Flutes, the Orlando Tin Whistlers and the Western Boys) to show off their talents.

Elias and his Zig-Zag jive flutes (supplied)

Ruthless record company talent scouts such as Rupert Bopape and Strike Vilakazi picked them up there, whisked them off to the studio, had them play tune after tune for an entire day, and put them back on the street with a few pennies for their efforts.

And it was at Zoo Lake where a young Albert Ralulimi of The Basement Boys and his fellow melody-maker Frans Pilane (who later became Mashiyane’s first guitarist) claim to have happened upon the schoolboy pennywhistle whizz Sponono Mashiyane on a visit to his aunt in Jozi from his home in Hammanskraal.

“At first we thought it was something like a bird singing,’’ Ralulimi relates in an 90-minute documentary I made on these musicians in the mid-1990s entitled The Whistlers, “but when we looked behind the bush we saw this young boy lying on his back playing the most beautiful sounds.”

The rest, as they don’t often say, constitutes a still rather arcane chapter of our musical heritage.

Born in New York, a so-called “diplomat brat’’, of the few aspects of South African culture in my first years that I could ever vividly recall, was this King Kwela record and Miriam Makeba’s debut album in the US.

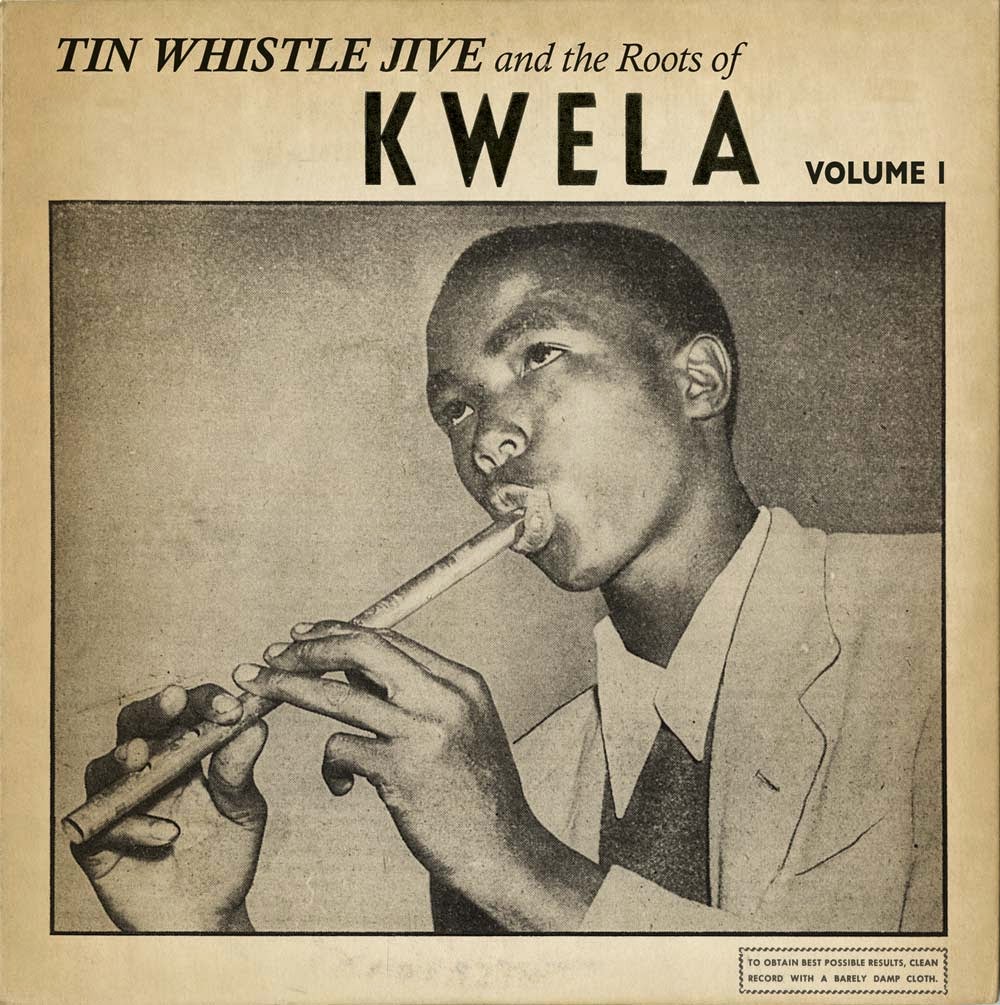

‘Tin whistle jive and the roots of Kwela’ Volume 1

Not only the bright burst of blue-green from Mashiyane’s Sunday-best shirt splashed across the backdrop of Ndebele patterning on his album cover. Or a glistening young Makeba tightly wrapped in teal and lilac in full Sophiatown swing on hers.

But rather the cuttingly clear tone, the piercing pitch, of both voice and whistle wafting up to my room in the early hours when the dregs of the consular corps get-togethers staggered about in an awkward cross-cultural side-show of sentimental longing for The Homeland.

Unwittingly of course, the white folks downstairs – bouffant hairstyles unfurling and wine splashing on to the imported carpets as they battled to emulate the Ghetto Jive – would help trigger my dedicating a hefty chunk of my life to traversing the African continent to research, document, film, play and write about its music.

But even after years of being regaled with romantic narratives about my real country in an attempt to instil some form of national pride in me there in the Western world’s leading urban wilderness, the “Dingaan’s Day” braais on a snow-splattered porch in Larchmont NY didn’t quite do it for me.

With scant tangible proof of South Africa’s existence, these two albums were a security blanket of sorts.

I could see, feel, touch, smell and, most importantly, hear all about the supposed Shangri-La in all its multi-chromatic sublimity. There were other records too, but none so aurally soothing or to my young eyes so prismatically explosive.

Compared to the mid-century self-importance, even austerity, of the Jim Reeves, Everly Brothers and Marty Robbins covers, the unaffected zeal and flourish of the township-bred contingent was a fresh breeze.

And with all the crew-cut, denim-clad kids carefully (Chuck) Taylor-ed to All-American perfection at Chatsworth Primary in Westchester County as peers, I struggled to identify with a colourless record sleeve hosting an eight-year-old Manie van Vuuren (or Viljoen or Van Rensburg) with parted hair flattened to the pate brandishing a concertina. So Mashiyane and Makeba it was.

Ironically, Spokes, eventually the principal poster image of Pennywhistle Jive and one of its chief exporters, was also the primary reason for the format’s demise.

As soon as he laid down his whistle and picked up the saxophone, every budding township whistler wanted to follow suit, and Kwela as a musical style died as abruptly as it started.

Born from a disparate blend of imported American big-band Swing and its local offshoot African Jazz, influences from the Irish Jig and Scottish military Fife and Drum bands, traditional Afrikaans Boeremusiek, rural African cattle herding calls and the cyclical hum of our first home-brewed urban styles such as Marabi, it scarcely existed for a decade from the early to late 1950s.

Yet, somehow the sprightly warbling turned out to be more typically South African than Lederhosen is German or foie gras French. I remain convinced it is so inextricably woven into the collective euphonious South African subconscious that you could play Ace Blues or Kwela Spokes off this album to a South African infant born in Iceland this very afternoon and you’d probably find its fingers starting to click right away.

But sadly, until his death, Mashiyane remained largely unrecognised for his broader significance as a cultural contributor or that his infusion of brass into the jaunty Kwela riffs inadvertently represented the birth pangs of an entirely new South African urban musical style later to become known as Mbaqanga.

Dropped off daily by his driver at the Mai Mai beerhall in downtown Johannesburg, Spokes slowly sipped his way through enough Limosin brandy to guarantee him an early grave.

So, from at least one person that will never forget your worth, here’s another almighty ‘’cheers’’ to you bra Spokes, your whistles’ wondrous wailing will certainly be accompanying me all the way to my grave and beyond as well.

***

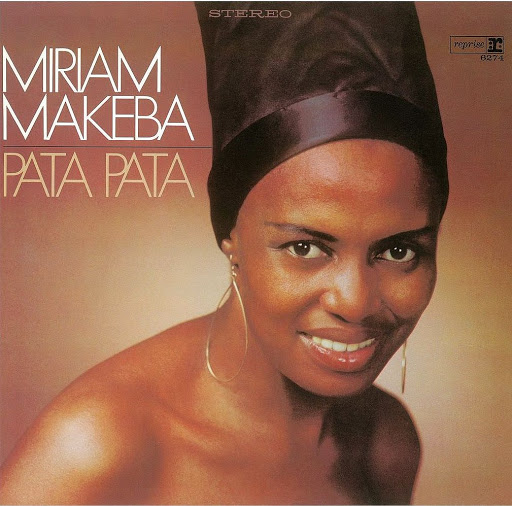

Miriam Makeba

My relationship with Makeba turned out to be an even more personal one because my father was dragged into the fray.

Fast forward some two decades from New York – after having been mesmerised on a daily basis by the flashy AmaPantsula-like steps of the Marrabenta street-groups in Mozambique during primary school years, and discovering the shops, backroom shebeens and eventually Steeve’s Record Centre in Marabastad and as a high-school boarder in Pretoria.

Throughout my secondary education, Makeba’s music was banned from SA shop shelves and airwaves, but during my second year of high school my father was posted to Germany, and on a jaunt to Italy a friend from Munich introduced me to Miriam’s driving protest Own Piece of Ground.

The lyrics were penned by well-known local SA folk singer Jeremy Taylor, best known for his genial spoof of white South African suburbia, Ag Pleez Daddy.

The prose, though rather naively reflective of the collective white South African dread of possible black reprisal (aka “Swart Gevaar”) for centuries of oppression, is nevertheless poignant – and Miriam’s cover catapults it into a next-level refrain of bitter dissent.

I had already been adequately roused by her strident anthem Hapo Zamani with its swaying Swahili intro, caustic indictment of the amabhule (boers) and impassioned plea to return to her birth land (“buyeye mama!’’). But this bold anti-apartheid statement of oozing resentment with its menacing end promising bloody revenge, constituted a matchless gut-blow:

But some people say now don’t you worry

You can always find work in the white man’s city

But don’t stay too long and don’t stay too deep

Cause you’re bound to disturb the white man in his sleep

White man don’t sleep long and don’t sleep too deep

For your life and possessions how long will you keep?

For I’ve heard a rumour that’s running around

Of the black man still wanting

His own piece of ground.

As students at one of the most prominent breeding grounds for Afrikaner Nationalism and racist indoctrination, we knew all about the Swart Gevaar (however watered down since its real-and-present-danger Bloedrivier days, to an embarrassingly transparent justification for the brutalities of apartheid by the time we were coming of age).

But apart from ruffling all the defensive fibres instilled in me since birth, the song also offered me for the first time, a sobering glimpse into the alternative reality of black South Africa. This was no paranoia-spewing propaganda thrust. It was a bristling rage and aching straight from the source.

But besides the fresh insights and sentiments, I was also adequately taken by all the lilting southern African melodies that so uncannily remained uplifting no matter how gloomy the context. I wanted more and I found it. All sorts of it. Almost every Friday afternoon on our afternoons off from boarding school, in Marabastad.

Marabastad was a sense-battering jumble of the latest township food, fashion and musical fare tacked onto the northern end of Pretoria central.

When Steeve’s Record Centre in Jerusalema Street first opened there it attract a slew of leftover aficionados of trans-Atlantic and African Jazz (ingenious indigenous revamps of US big-band Jazz and Swing), but the shop was soon stocked with a broader smorgasbord of local sound.

It was long before “cultural appropriation” became the swear words they are today and I was gleefully absorbed by the vinyl-stacks of Masekande (aka Maskandi/a or traditional Zulu street guitar music) Mbaqanga (the rapid-fire city-style and its vocal-based offshoot Mqashiyo or bounce), Isicathamiya (African choral call-and-response music) and Kwela. A bonus was meeting some of the self-taught township composers in person over frothing 5-litre plastic barrels of umqombothi at the local shebeens.

By the time I found myself on the arts pages at the Cape Times in the late 1980s I took a hard, unabashedly biased line in a weekly music column: all southern African township-generated music was cool – even if imposters such as Paul Simon sometimes intervened and dubious local crossover efforts were un-éVoid-able. (And apart from perhaps the fresh urban uprising of the “Jamesons Generation”, everything else was not so.) And when the opportunity arose to cover Miriam performing live on the Graceland tour, a car full of us joined the 30-hour long, 2,500km trek to Harare, Zimbabwe.

Cleaving through a heaving Rufaro soccer stadium to a decent vantage point just before sunset seemed fruitless until I was beckoned by press photographer Steve Hilton-Barber hanging from a lighting/sound scaffold to join him.

Once up there, he fished some homemade cookies from his flak jacket with a customary cat-like grin. And soon the mellow light draining through the African-print stage-covering from one of the dust-infused, deep-orange sunsets that linger so much longer than others only in Africa, I was swept up in a rare “Perfect Moment” that would have turned Spalding Gray green.

Before it erupted, an uncustomary calm coated the crowd as Makeba floated into view in flowing mauve-and-silver flanked by ex-husband number three (Hugh Masekela) and a beaming Ray Phiri poised to fire his next rhythmic salvo.

Despite my father’s likely role in the curtailing of one of Africa’s most prominent musical careers and knackering of South African culture on the grandest scale, Makeba’s status as one of Africa’s most significant musical icons, could not possibly be diminished.

Apart from two appearances in Botswana and Lesotho in the early 1980s, it was the closest Miriam had been to home in nearly three decades. And when she launched into the deliciously languid opening of Soweto Blues, the anguish and yearning had both Steven and me perched there on the makeshift pylon, dragging our soggy eyes across our shirt sleeves.

Back in the office in Cape Town, Miriam’s autobiography lands on my desk for review. I am assailed by a gnawing apprehension as I approach the section where she wishes to return to South Africa for the funeral of her mother and two family members who died during the Sharpeville massacre. It rapidly morphs into a sweeping nausea as I read how the consular official in New York stamps “denied” all over her passport and I double-check the date. It is 1960. Who was the South African vice-consul normally tasked with such duties in New York in 1960? My father, Izak David du Plessis.

A swirling mix of mounting shock and shame is nearly overridden by the almost laughable irony. Here I was quite haughtily projecting myself as a dedicated proponent of African music and my own father was the miscreant responsible for casting the Empress of African Song into permanent banishment.

Still suitably thrown, I phoned him at the Embassy in Helsinki. “I’m reading Miriam Makeba’s biography. Are you really the official that stamped her passport at the consulate in New York? ”

He fobbed it off without the slightest hint of defensiveness: “There has never been any South African in the history of our country that has been refused entry into South Africa.” He suggested that hers, as was the case with other cultural refugees, was a self-imposed exile.

Like many others of his generation, my dad could be a bastard at the worst of times. But as a result of some clumsily construed Calvinist pact he had made with himself as a child, he never lied, swore or spoke bad about others (all of course standard traits for the exacerbation of bastardness).

At first glance, my father’s claim, frustratingly, seemed to be technically sound. During those years there did not appear to be any record or rule that forbade South Africans to return to South Africa whenever they wished.

In a renewed attempt to shake the perplexia, I phoned again. The United States refused her re-entry after a trip to the Bahamas, he explained. So apparently did France because of her association with Guinean President Sekou Toure. But South Africa, no, never. “This was all on record,” I cried. There were pictures of her passport with the glaring red “DENIED” stamp splattered all over it.

“That’s what happens to everyone’s passport at all the missions of all the countries on Earth when the passports expire,” he responded patiently. A renewal was way overdue. He even helped her apply for a new one. And assisted her daughter and Hugh Masekela to attain their US visas too.

So, this was all an elaborate staging, a widespread publicity ploy by the so-called South African exiles to evoke empathy with “bleeding-heart liberals” around the globe?

Whereas he, pure as the driven snow, was simply trying to help? Well, he didn’t know about all that, he responded disconcertingly. He liked her, she seemed like a nice enough person. “I bought her record, you know. Beautiful voice,” he trailed off – seconds before an unnerving image flashed through my hind-head of him, whisky glass aloft, doing the late-night Pata Pata.

‘Pata Pata’ Miriam Makeba

The part he conveniently omitted from the discourse of course, was that the likes of Miriam Makeba or any other dissident voice would in all probability have been be arrested at the airport on their arrival as an enemy of the state and schlepped off to the nearest detention centre by the apartheid gestapo – complete with a curt statement soon after lamenting an accidental six-storey plunge from some nondescript downtown building with mirrored windows.

In 1990, myself as arts editor of the newly incepted Vrye Weekblad, and The Argus’s contemporary music editor Marc Le Chat, were the first to interview Miriam after her re-entry into South Africa. Settling into a cubicle at an eatery in Sandton City there initially seemed to be little evidence of this woman having weathered a mother who named her Zenzile (“you have only yourself to blame”), rampaging apartheid, kidnapping and assault at the hands of Sophiatown gangsters, five marriages (among others to an abusive alcoholic and a self-aggrandising leader of the US Black Panther movement, Stokely Carmichael), a plane crash, breast and cervical cancer, crushing psychotic episodes (or “amadlozi” – “spiritual possession”) and the death of her only child Bongi during childbirth (or a backroom abortion depending on which tale you care to believe). She seemed to still be glowing with hope and energy.

But as the lunch dragged on, a weariness and sense of defeat seemed to sink in, directly proportional to the white-wine levels.

It became increasingly difficult to see the sassy young songstress with her bubbly red Sparletta bottle holding forth on the Gallo Music rooftop with her fellow Skylarks (a South African female vocal dream-team if ever there was one with Miriam, Abigail Kubeka, Letta Mbulu, Mary “Kolokoti” Rabotapi, Mummy Girl Nketle – until imprisoned for theft – and occasionally Drum Magazine cover favourite Dolly Rathebe).

Other long-held images too, become less discernible: the measured anti-apartheid orator at the United Nations, the high-flying social associate of Sekou Toure or the stern castigator of her activist spouse (Carmichael) for pretentiously dressing down for the masses in their upmarket New York apartment: We have spent our lives struggling to wear proper clothes and look at you…

An evergreen grace and ceaseless sense of style still attested to the once swanky Seventh Avenue fashionista who launched the Afro hairstyle as an international phenomenon – or sultry African Monroe performing at JFK’s 45th birthday.

Residues of the fierce human rights campaigner, reluctant gangsta-moll, rue-wracked mother or winsome shebeen-nymph surfaced as she alternatively slumped into fond reminiscence or was jolted from unsettling mental snapshots – but any such ephemeral, pop-up personas were eventually overshadowed by the battle-scarred legend before us buckled by grief, fury, regret and sorrow.

Yet, none of it mattered. Despite my father’s likely role in the curtailing of one of Africa’s most prominent musical careers and knackering of South African culture on the grandest scale, Makeba’s status as one of Africa’s most significant musical icons, could not possibly be diminished.

Not only her vocal abilities (I still find there is no more arresting auditory experience than that of a young Miriam Makeba in her musical apex), but as a symbol of sheer human endurance in the face of astonishing adversity.

Alternating effortlessly between below-the-belt husky and disarmingly dulcet, Miriam might not have been possessed of an Erna Sack-like range, but she made up for it with an earthy fervour. Even in her dotage, the mud-cracked cry could raise the hairs on my forearm.

So, here’s to you too, dear Grand Madame of African Anthems, know this as your call keeps rebounding through time off the outer walls of the universe, you certainly helped shape a better part of me that would have otherwise been lost. DM/ ML

Footnote: Before it was called Kwela the music was termed Pennywhistle Jive by artists and record companies alike and, according to the late great pennywhistler, saxman and music producer West Nkosi, white people – and particularly the so-called Joburg “ducktails” – were responsible for the former term. For foreign folks and South Africans that don’t know this yet, Kwela (or Khwela) which literally means “climb” in Zulu, was used in reference to the large yellow police vehicles commonly utilised to arrest the young pennywhistlers on the city streets for public disturbance. Upon hearing the commands by the police to “get up’’ or ‘’climb” into the vans, the ducktails – often self-employed as lookouts for the urban troubadours – would shout, “Here come the kwela-kwela vans”, and the term was later used to describe both the vehicles and the music itself.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider