An increasingly prominent aspect of political campaigning is digital advertising, particularly on social media platforms, where targeted adverts allow parties and candidates to reach specific demographics and engage with voters directly.

Digital ads have revolutionised how information is disseminated and how people are targeted through highly personalised messaging.

Using advanced data analytics and behavioural tracking, companies, organisations and political parties can tailor adverts to specific audiences, based on age, location, interests and browsing history.

This is called microtargeting – and in the context of elections, it can sometimes be quite dangerous.

Adverts can be targeted to young, urban professionals, retirees or rural communities with tailored messages to address each group’s unique interests.

While those running these ad campaigns will argue that microtargeting offers a better return on their investment, the intended and unintended consequences of such actions can be locking people into echo chambers, where individuals are only exposed to information which reinforces their existing beliefs and prejudices.

Take, for example, the 2016 US election, where Russian-linked entities targeted political ads on social media platforms to specific voter segments to sway opinions on key issues or candidates. This microtargeting approach was intended to amplify political polarisation and influence voter behaviour.

Analysing Meta’s ad library

In an attempt to increase transparency in digital advertising following criticism and concerns about the opaque nature of political adverts on its platforms, Meta in 2019 launched its ad library which catalogues all political ads running on Facebook and Instagram, and provides data on spending, demographics and funding sources.

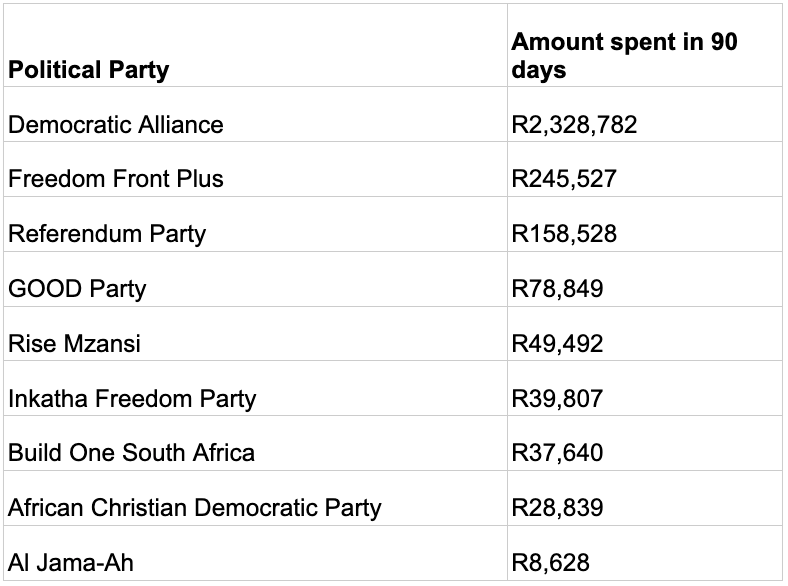

Amounts calculated according to the total spend per advertiser in the past 90 days.

The DA is the biggest digital ad spender by far. It has spent more than R2-million on 799 digital adverts on Meta platforms in the past three months, under its campaign theme #RescueSA.

During this timeframe, it has targeted audiences based on their location, with an increase in adverts targeting people living in North West (specifically Derby, Ventersdorp, Tlokwe, City of Matlosana and Kroondal) and Mpumalanga (Govan Mbeki District Municipality, Umjindi, Steve Tshwete Local Municipality, Mbombela and Emalahleni)

The Freedom Front Plus (FF+) has spent just under a quarter of a million rand, with 39 digital ads over the past 90 days. It identified voters in the 18-35 age group as its primary audience, with 98% of the party’s ads being used to target this category.

The FF+ is also microtargeting its ads based on information it receives about audience interests. For example, people who have liked the Kyknet, Huisgenoot, and Afrikaans Is Groot pages on Facebook and Instagram are likely to encounter FF+ adverts.

Rise Mzansi, which spent close to R50k on 23 adverts over the past three months, has targeted only women aged between 27-45. This specific microtargeting may align with the party’s policy manifesto that includes a commitment to tax breaks for single mothers.

Unknown players influencing our elections

Interestingly, the Meta ad library also provides insights into organisations that are not registered political parties but are running extensive election-related adverts. Collectively, these pages – Ask South Africa, Dear South Africa, Save Our South Africa, Pledge South Africa, We Are The People and Constitutional Hill TV – have spent more than R500,000 on election-related ads on Facebook and Instagram over the past 90 days.

This is how they have been microtargeting voters:

- Ask South Africa: This page was created in May 2023 and has spent R233,167 on 19 adverts. All the adverts are targeted at people who live in the Northern Cape, with nine adverts specifically related to load shedding. Ask SA identifies itself on Facebook as a “market research consultant” and all of its ads have been paid for by the Freedom Advocacy Network – a project of the SA Institute of Race Relations.

- Constitutional Hill: This page should not be confused with the actual Constitutional Hill located in Braamfontein. An analysis of its adverts shows no connection to the historic site. In 30 days, starting early April, it spent R114,081 on 29 adverts. One ad noted that “a vote for Gayton McKenzie’s PA is a vote for the ANC to enable corruption while people can barely afford food prices.” Additionally, some ads include the term: “The DA difference” – with a positive sentiment towards the Democratic Alliance.

- Save Our South Africa: Over the past six weeks, Save Our South Africa, a page created in March 2024, ran 72 adverts at a cost of R99,004. Its website is opaque with no information about funders or the people who work for the organisation. Under About Us, Save Our South Africa claims that it is “not just some movement; we’re a community standing together to give our people what they deserve”. A scan of its adverts indicates that the group is concerned about education and policing. One advert claims: “12,000 yearly cases of school-related corruption. Take back our schools. #YourVoteCanSaveSA”. All of Save Our South Africa’s ads target women aged between 18-40.

- Dear South Africa: This is a popular Facebook page with more than 200,000 likes, which was created in 2018. A scan of the Dear South Africa website notes it is a non-profit platform that encourages the public to “co-shape all government policies, amendments and proposals”. Dear South Africa boasts that it has “many successful campaigns and have amassed a considerably large active participant network of over 1 million individuals across the country and beyond.” The website does not provide any information about people who work at Dear South Africa, who its funders are, or where it is based. In the past 90 days, it spent R79,090 on 32 adverts. Some of its ads made the following false claims: “The frightening reality is that the IEC is now trying to take away your democratic right to vote for a party that will guarantee you that right to vote for a referendum on Cape independence.” According to the data, this advert reached between 125,000 and 150,000 people in the Western Cape.

- Pledge to Vote SA: This page has more than 14,000 followers and was created in January 2023. It’s run 37 ads in the past three months, costing R46,185. There is a high ad spend on groups aged 18-35 who have shown an interest online in issues relating to “elections”, “activism”, “voting”, “community issues” and “social change”. Pledge South Africa has been running adverts to these targeted groups with a negative stance on BEE and the National Health Insurance – which are policy priorities of the current government. Some of its ads included the following messaging: “The National Health Insurance (NHI) is a ticking time bomb, threatening to nationalise your private health insurance, hospitals, and doctors. The NHI will compromise the health and wellbeing of you and your loved ones. Pledge your vote in the upcoming 2024 election to vote out the NHI.” Although the NHI Bill is controversial, claims that the NHI will “nationalise private health insurance” are factually incorrect. At the bottom of the About Us page on its website, Pledge to Vote SA has been identified as an initiative of the Institute for Race Relations (as has Ask South Africa, above).

- We Are The People: This page was created in early April 2024, with adverts kicking off on 26 April. In a matter of days, R14,088 has been spent on advertising. We Are The People notes that it is a “voluntary association formed to mobilise citizens to continuously participate in democracy”. When analysing a video advert that it released, the messaging is strikingly similar to that of Rise Mzansi. The video features a segment about the economic pressures faced by single moms (a key policy issue for Rise Mzansi). Also that “we need a new generation of leaders” (Rise’s main campaign theme is #WeNeedNewLeaders). Perhaps the most revealing aspect is the inclusion of the statement, “Let’s vote for change, and to make 2024 our 1994” – a statement coined by Rise Mzansi. When analysing the micro-targeting data, We Are The People is targeting the same demographics as Rise Mzansi – women aged between 27-45. The We Are The People website does not disclose its funders.

In each of the above case studies, none of the adverts in use is directly encouraging users to vote for a particular party. However, from the messaging that is used in the ads, especially in the case of Ask South Africa, Constitutional Hill, Pledge To Vote SA and We Are The People, there are subtle and not so subtle attempts to persuade you to vote for certain political parties. The Institute for Race Relations – which is funding political ad campaigns for both Ask South Africa and Pledge to Vote SA – allegedly has links to the Democratic Alliance.

Non-profit organisations, community associations, think tanks and lobbying groups are not barred from endorsing political parties and leaders.

In our constitutional democracy, individuals and entities have a right to give their support to parties or persons that best align with their interests. However, the key to this is transparency and honesty.

Using digital platforms to microtarget voters for political purposes without disclosing links to current political parties is not only unethical, but also undermines the tenets of our democracy.

Preserving democracy in the age of digital advertising

The data from Meta’s ad library illustrates the importance of the electorate being aware of how it is being targeted.

Different strategies are being employed in political advertising to microtarget voters and persuade them to vote in particular ways. In this light, voters have to be sceptical and question the information they encounter online.

Always verify facts, question the intentions behind the ads that you are seeing and ask why you may have been targeted to see those ads.

The transparency measures introduced by platforms such as Meta’s ad library are a positive step, but more regulation is needed to ensure fair practices. This includes stronger oversight of political ad funding and enforcing transparency requirements on political parties and those linked to them.

Ultimately, protecting the integrity of elections in the digital era demands vigilance from voters, regulators and platforms alike, ensuring that technology serves democratic values rather than subverts them. DM

Author’s note: As stated above, I relied solely on the Meta ad library to conduct this analysis. On 29 April I was temporarily blocked by Meta from accessing the library due to allegedly “misusing this feature by going too fast”. This is a completely bizarre reason to block a user’s access. At the time of publication of this piece, I am still locked out of the library.

IRR tentacles everywhere. I’d love to see an article looking into its major funders and their potential motivations.

My personal feeling regarding the IRR is a bit different. They are not shy regarding their ideology. If they started pretending to be a “gift of the givers” type organisation, I would definitely want to know what’s up.

Cool, but why go to the trouble of creating all these fronts in order to push that ideology? While the Freedom Advocacy Network’s website is candid about being an IRR project (it’s actually just a page on the IRR’s site), the YouTube channel is not, and the average person stumbling onto that channel is not going to visit the website for due diligence. It’s astroturf.

Also, weirdly, the website says that the FAN project ended in 2022. So why do they continue using the entity to fund political ads?