GUEST ESSAY

Money and science — an uncomfortable codependency

Money comes with strings attached. And when it comes to fundamental research, those strings are often political, not scientific – illustrating the tragic tension between what may be best for human knowledge versus what may be best to garner political support.

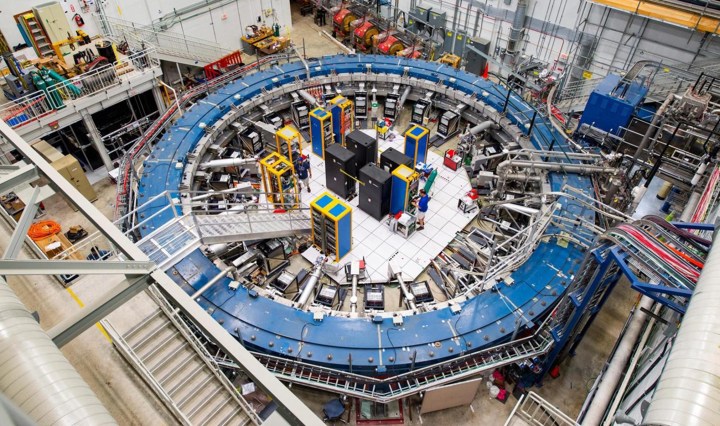

On a recent trip to Amsterdam to visit family, we were given a tour of Nikhef, the national particle physics institute which collaborates with the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland – a circular tunnel under the earth that smashes protons into each other at close to the speed of light to detect what spews out, and how it may help us to understand the universe. (Full disclosure – the tour was conducted by my daughter, a PhD candidate in particle physics.)

Why in the world would anyone spend money and time on this abstruse and expensive project whose goals and successes (and failures) to date are understood by, well, almost nobody?

I have more than a passing interest in the LHC and the physics that it has been trying to unmask since it was built between 1998 and 2008, at a cost of around $50bn in capital and operating expenses to date.

Fundamental physics has always seemed to me to be an irrepressibly noble pursuit, floating high above the common and immediate concerns of humanity, such as shelter, nourishment and health, and after that, perhaps, ideology, politics, economics, profit and the rest.

My interest, I suppose, is sparked by a faint envy of those who understand the strangeness and counter-intuitiveness of the worlds these particles inhabit, as well as amazement at the apparently endless nature of the physicist’s explorations – every small advance seems to open a swarm of new questions; the horizons of enquiry seem to constantly expand.

On the ground floor of Nikhef there is a mini-museum of sorts, chronicling the history and current development of the LHC. It is housed in the centre of a campus corridor surrounded by various large-windowed labs. Students and academics scoot among the inscrutable exhibits – magnets, coils, electronics, detectors, scale models – on their way to and from lectures, offices, the cafeteria and working labs filled with furrow-browed scientists building and testing stuff.

The Large Hadron Collider is not the only player in this game.

There are other colliders, like the earlier Tevatron in the US. There are newer, bigger and badder (and more expensive) colliders on the horizon, like the 100km Future Circular Collider, which is another proposed European initiative.

The Chinese, who have emerged as an aggressive competitor in physics, have their Circular Electron Positron Collider which should be ready in 10 years.

And there are a slew of other, non-collider experiments also sniffing at the nature of the universe – from vats of liquid Xenon gas deep under the earth in South Dakota, to massive telescopes taking up residency both down here on Earth and out there in the heavens.

Which is where the grubby business of money raises its ugly head.

Imagine you are a physicist who has been granted an audience to pitch your new experiment to Congress, or to the European Commission purse-holders, or to Chinese Communist Party apparatchiks.

It might go something like this:

“My colleagues and I, after years of research and discussion, would like to build a big physics whatsamajig.”

“Ah. What’s it for, this whatsamajig?”

“We may find a new tiny particle.”

“You MAY find it?”

“Er… yes. I have a document here. It is only 7,000 pages – we had a good editor. It explains why we may find it.”

“What happens if you don’t find it?”

“Then we will also have learnt something.”

“How much is this going to cost us?”

“Only $15-billion over the next 20 years.”

“$15-billion??”

“Yes. Plus the annual $6bn in operating costs.”

“You’re shitting me.”

“No really, that’s not expensive when you consider how much we will learn. And we really sharpened our pencils before budgeting. We cut out all the fat before we came here.”

“What will you learn if you find it?”

“We will learn why there is something rather than nothing.”

“Get out of my building. Now.”

You see the problem. In fact, it went something like that when the US Congress decided to direct funds towards more certain outcomes rather than pay for a supercollider in the 1980s, leaving the EU to take the lead.

Other projects have also not seen the light of day – too many to mention.

The system of research funding is gnarly and fraught and highly contested, from the smallest university lab to the grandest of global projects, such as the Earth BioGenome Project or Phase 2 of the Square Kilometre Array, which has had its ambitions scaled back by the funders.

Money comes with strings attached. And when it comes to fundamental research, those strings are often political, not scientific – illustrating the tragic tension between what may be best for human knowledge versus what may be best to garner political support.

Most people sort of understand that fundamental research, usually the province of academic institutions and state largesse (as well as corporate-funded research programmes) can lead to discoveries or inventions that are useful to the average citizen.

The research that led to the Internet, for instance, was funded by the US Defence Department as a strategy to keep the country’s computers operating even if the country was under attack.

The same goes for the research that led to vaccines and solar energy and medical imaging and GPS and transistors and… all manner of wonders that touch our lives directly today.

But, if you ask the question “to what end particle physics?”, the only honest answer can be “because”. Because we don’t know enough. Because we feel a need to know more. Because that’s what we do, us humans. What we have always done. We have always wondered – what the hell is going on here? What is this stuff we see, hear, smell, feel? Where did we come from? Are we alone? Where is the edge? When was the beginning? Is there an end?

Which brings me to this thought, especially after gazing at the little Nikhef museum in a kind of stupefied wonderment. If I were sitting in that budget allocation meeting in the halls of power trying to balance the clamouring and competitive needs of a fractious citizenry, I would say to the hopeful physicist – how soon do you need the money for your whatsamajig and are you sure it’s enough?

Why?

Because. DM

Steven Boykey Sidley is a professor of practice at JBS, University of Johannesburg. His new book, It’s Mine: How the Crypto Industry is Redefining Ownership, is published by Maverick451 in SA and Legend Times Group in UK/EU, available now.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.