REFLECTION

A poetic pilgrimage in the footsteps of Roy Campbell

After it premiered in 1995, Anthony Akerman’s play about the charismatic and controversial poet Roy Campbell was performed to critical acclaim and garnered several awards. In this story, Akerman explains what drew him to Campbell and takes the reader on a literary pilgrimage that ends in a remote Portuguese hillside cemetery.

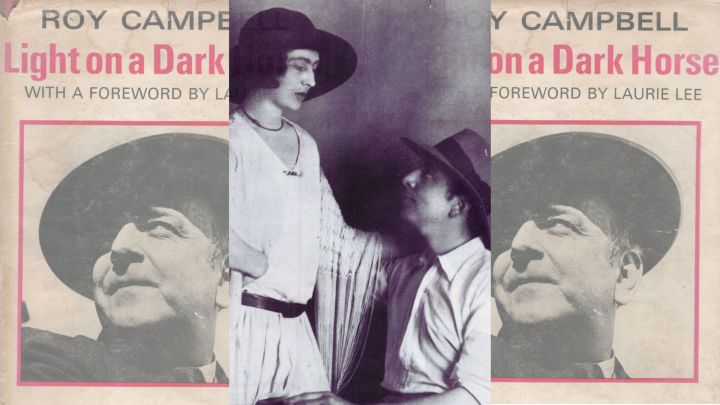

I’d been in England for a year and had just started experiencing the first pangs of homesickness when a South African friend lent me Roy Campbell’s Light on a Dark Horse. Campbell believed the only writing deserving of that name was poetry — and referred dismissively to his autobiography as an “autobuggeroffery”.

It’s a swashbuckling narrative, full of transparently improbable tall stories and achingly beautiful evocations of Africa that enhanced, rather than assuaged, my homesickness.

‘Light on a Dark Horse’ by Roy Campbell. (Image: Supplied)

Campbell was a contradictory figure. He was — in the words of the South African poet David Wright — “among cowboys a poet and among poets a cowboy”. He was also no stranger to controversy. As a convert to Catholicism in the 1930s, he sided with the church — and therefore Franco — during the Spanish Civil War. For this, he was labelled a fascist by the left-wing English poets Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender, WH Auden and Cecil Day-Lewis.

Not one of these “fire-eating belligerents”, as Campbell labelled them, had been on active service during World War 2, while Campbell had volunteered and insisted on being enlisted as a private. In retaliation, he created the portmanteau name MacSpaunday for the four of them, but he had a particular score to settle with Spender.

A few months before I was born in 1949, Campbell heard that Spender was going to be reading some of his verses for the Poetry Society in the crypt of the Ethical Church in Bayswater, London, and decided it was as good an opportunity as any to denounce his detractor. Fortified by more than a few drinks, he and several friends arrived at the venue — although it’s doubtful if they knew what he was going to do. Perhaps he didn’t know either.

As Spender was introduced to the audience, Campbell got to his feet, registered his protest “on behalf of the Sergeants’ Mess of the King’s African Rifles” and advanced on the stage. The audience could have been forgiven for thinking they were watching a French farce when Campbell flung open a door he thought would give him access to the stage and found himself limping off towards the lavatory. Yelling curses, he doubled back, climbed up on the stage, leaned on his gnarled walking stick and took a swipe at Spender. The blow clipped Spender’s nose, which began bleeding profusely.

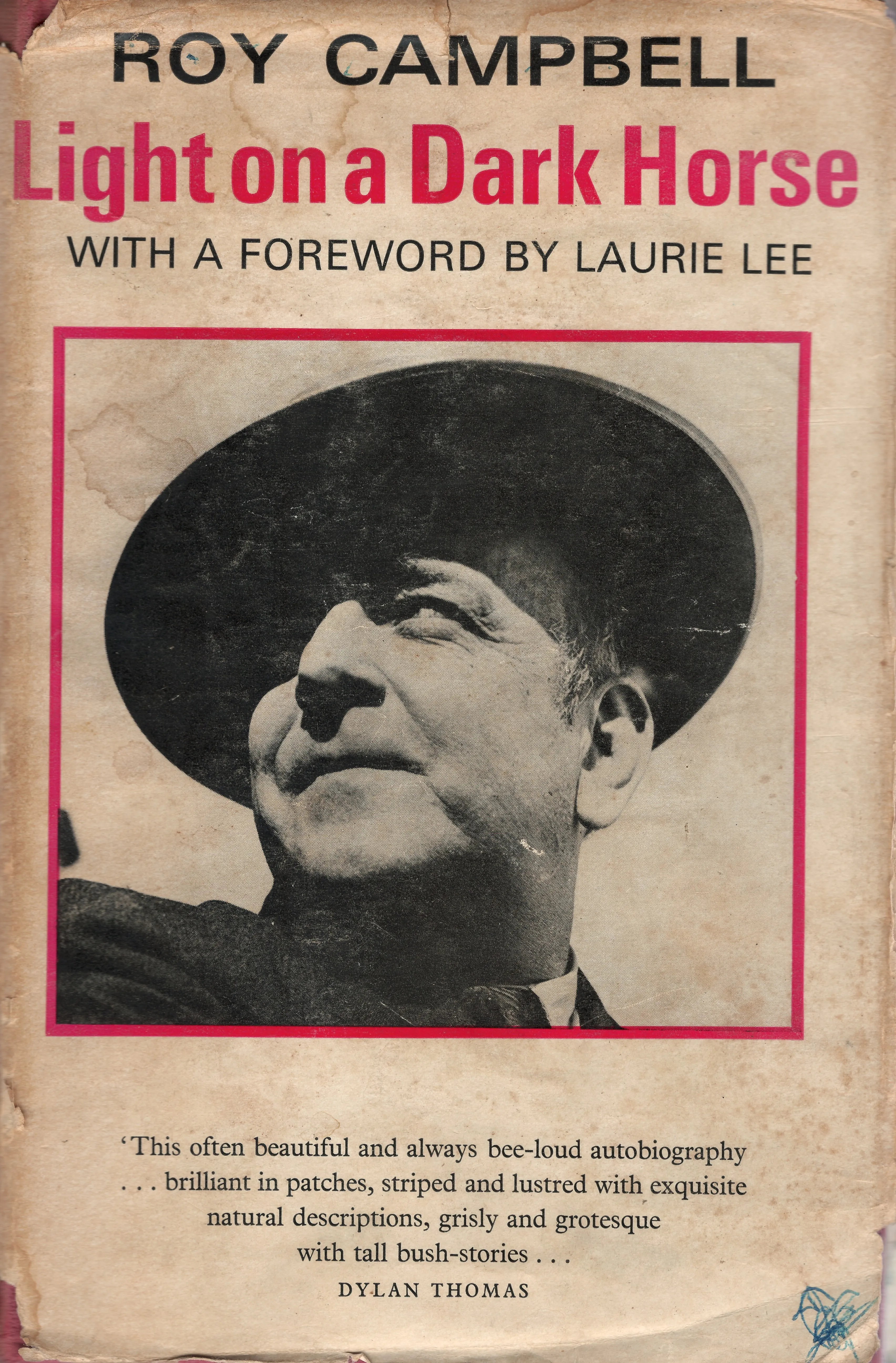

When Campbell stomped off, shouting — on Spender’s version – “He’s a fucking lesbian”, the organiser of the event offered to call the police. Spender demurred, saying, “He is a great poet; he is a great poet. We must try to understand.” I hadn’t heard this story when I was introduced to Spender and shook his hand at Poetry International in Rotterdam. That was 1982, the year Peter Alexander’s Campbell biography appeared. In it, he retells this story and, for the first time, went public with another — a story Campbell had done his best to suppress since 1927, when he and his English wife Mary had returned to England after a somewhat disastrous stay in South Africa.

Peter Alexander’s biography of Roy Campbell. (Image: Supplied)

It was an event that, according to Alexander, “scarred the poet’s mind and affected his verse to the end of his life”. When Mary told Campbell what was going on, he caught the train to London, no doubt intent on getting blotto, and bumped into the author CS Lewis in a pub.

They were only slightly acquainted, but Campbell felt the need to unburden himself. After he’d done so, Lewis remarked, “Fancy being cuckolded by a woman!” Mary had fallen in love with their hostess, Vita Sackville-West, and it would have destroyed the Campbells’ marriage had the predatory Vita not tired of Mary and moved on to her next sexual conquest.

I felt an affinity with Campbell. We’d both been born in Durban, had grown up in Natal, had left the country as young men and — albeit for different reasons — had lived in exile. Mary disliked South Africa and, after their 1925/6 sojourn, would never return. Campbell couldn’t live without Mary so, apart from three brief subsequent visits, he never saw his home again.

During the war, he was shipped out to serve in East Africa and docked in Durban on the outbound and homebound journeys. In 1954, he flew out to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Natal. On that trip, his brother George drove him out to visit their mother in Botha’s Hill and passed my parents’ home in Hillcrest while I was playing cowboys and crooks. If I’d been hiding near the stone gatepost with my cap gun, I may have seen him driving past.

***

When Mary wouldn’t give up Vita, Campbell fled to Provence. She eventually joined him and, for several years, they lived in what he described as that “little bit of Africa in Europe”. From there the family moved to Spain where they converted to Catholicism. Campbell believed that’s what saved their marriage. Except for the war and post-war years, the Iberian Peninsula became their permanent home. It was his surrogate South Africa.

Mary and Roy Campbell reunited after Vita. (Image: Supplied)

In what the writer Laurie Lee described in the 1930s as Campbell’s “expatriate heart”, he remained unalterably South African. Paradoxically, the longer he was away from home, the more pronounced his South African accent became. The poet Uys Krige said it was “worse” than his own Afrikaans accent and eventually became so thick “you could cut it with a Knysna notch saw”.

Alan Paton believed his prolonged absence from home adversely affected his poetry. After his death, Mary showed Paton — who at the time was contemplating writing Campbell’s biography — notebooks kept during Campbell’s final years. Paton concluded they were “the notebooks of a man who wants to write and cannot”. They were strewn with unfinished fragments, attempts to conjure up the lost Eden of his childhood — “Stones of the Berg”, “Stone of the Dragon, the maternal womb”, “The Dragon Stone that shaped my course and doom”. The word “coffin” recurs frequently and is referred to as “my overcoat of firewood”.

A fatal crash

In 1957, the Campbells spent Holy Week in Seville. Mary told Alexander that Campbell was not his boisterous self but was unusually serious in his devotions. Driving back, just south of Setúbal in Portugal, a front tyre burst, their Fiat 600 crashed into a tree and, by the time he and Mary had been dragged from the smoking wreck, Campbell was dead. This happened on 23 April — the date on which Shakespeare died. Campbell was 56. He was buried in São Pedro cemetery, not far from their home near Sintra.

It seemed desperately sad that one of South Africa’s greatest poets should have been buried so far from the country that shaped him, the country he loved. And I thought of other South African writers — also exiles — who’d died and been buried far from home: Nat Nakasa in Ferncliff cemetery in upstate New York and Alex la Guma in Havana, Cuba. I wasn’t contemplating my own death, but I knew I didn’t want to be buried in Amsterdam.

By mid-1988, I’d started making notes towards a play about Campbell.

At the time I was working as a literary manager for the Civic Theatre in Rotterdam and as I stared out of the train window on the daily commute, I blotted out the polder landscape and imagined Roy Campbell making a theatrical entrance on an empty stage, wearing a Spanish Cape and Córdoba hat. What was he going to say? Perhaps one of his tellingly provocative quips, such as: “Translations, like wives, are seldom faithful if in the least attractive.”

A year later, I still hadn’t settled on my story, but I knew the heart of it would be a love story. That’s something else I had in common with Campbell — turbulence in affairs of the heart. As it happened, I was going through my first divorce — but not because my wife had gone off with another woman.

I was experiencing emotional upheavals on another front as well. I’d just traced my birth mother in Cape Town and she was prepared to meet me. But there was one small problem. I’d become a Dutch citizen and, two years earlier, had been denied a visa for South Africa.

In 1983, I’d received a government subsidy to stage my anti-war play Somewhere on the Border. I suspect that decision was based on the politics of the play rather than such nebulous considerations as artistic merit. I’d just directed a showcase production of my play A Man Out of the Country. That was of some interest to Dutch audiences as it was set in the exile community in Amsterdam and the central conflict played out between a Dutch woman and her South African boyfriend. But I knew that a play about a South African poet with problematic political views would be of less than zero interest to those who called the shots in Dutch theatre.

Even if I couldn’t go back to South Africa, I hoped my play might find its way there. I based this expectation on the controversial success Somewhere on the Border had enjoyed back home in 1986/7. It had even been nominated for a Dalro Award, so maybe some producers or directors would be sufficiently interested in reading it with a view to staging it. I was thinking Market Theatre rather than state-subsidised theatres. But then again, the Market had passed on Somewhere on the Border and it was eventually presented by a state-subsidised theatre.

My notebook reveals that in January 1990 I was trying to wrestle the Campbell material into some kind of dramatic shape, which suggests I hadn’t expected FW de Klerk to make any surprising announcement on 2 February. He did and that changed all my plans. After Nelson Mandela walked out of prison, I immediately applied for, and was granted, a visa. I’d still hoped to get something down on paper — a synopsis at least — before going home. I didn’t, as there were just too many distractions.

Finding a title

But I did accomplish one thing. The British playwright Howard Brenton kept telling me I needed to find my title. He was right. Not all writers work that way but, if I find what I feel is a good title, it helps me focus and points me in the right direction. I eventually found it in one of Campbell’s poems.

In 1939, reviewing Flowering Rifle — Campbell’s unreadable paean to the Spanish junta — in the New Statesman and Nation, Spender labelled him a talking bronco. Campbell gleefully embraced the intended insult as a compliment and wrote a poem called Talking Bronco in which he took aim at Spender and MacSpaunday. Asserting the correctness of his position, he wrote, “So History looks the winner in the mouth / Though but a dark outsider from the South”. So there it was: Dark Outsider.

When Campbell disembarked in Durban in April 1943, it had been 16 years since he’d set foot in his homeland. When I landed at Louis Botha Airport, I’d been away for 17 years. Being at home again, surrounded by family and friends, was a profoundly emotional experience. I was also reunited with my birth mother for the first time since I’d been a baby, as well as biological siblings and cousins.

But I hadn’t forgotten Roy Campbell.

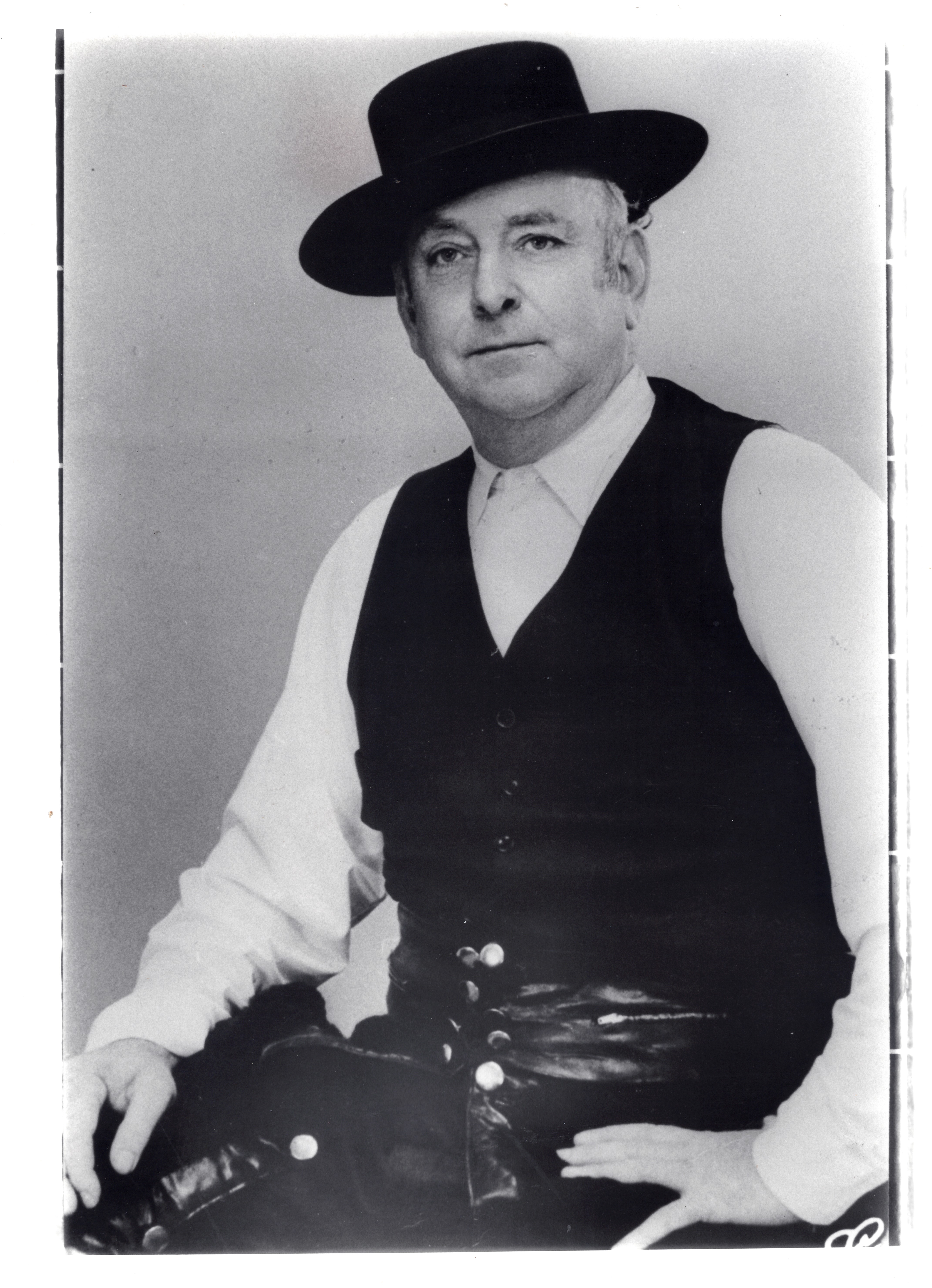

Roy Campbell. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature)

Although my parents had subdivided their property, the old stone gatepost where I’d dry-gulched my friends while playing cowboys and crooks was still there, not far from the Old Main Road where the Comrades run their marathon every year. That’s where I like to think I saw Campbell on his way to Botha’s Hill, sitting in the passenger seat of George’s Buick Roadmaster and, to me, looking every inch the Mexican bandit with his Córdoba hat tilted at a rakish angle. In later life, Paton also lived in Botha’s Hill and that’s where, in 1974, he opened his front door and scowled — as was his wont — at a young Peter Alexander.

Alexander was a South African postgraduate doing research on Campbell for his Cambridge PhD. For several years, Paton had been collecting material for his planned Campbell biography, although he’d not yet begun writing. According to Alexander, Paton had found members of Campbell’s family uncooperative and even devious. The previous year, he’d visited Mary in her simple country house outside Sintra, which is when she showed him Campbell’s last notebooks.

A wealthy poetaster called Rob Lyle — who’d first tried to elope with Mary and then married Campbell’s daughter Anna — was the litigious custodian of family secrets and, after speaking to him, Paton said he’d sooner “interview an iceberg in a typhoon”. Yet, rumours of extramarital affairs could not be ignored and the biographer has an obligation to write the truth. What the straitlaced Paton hadn’t anticipated was that Mary had had lesbian lovers. The difficulty he faced was that she wouldn’t volunteer any information and he was too prudish to broach so distasteful a subject.

Although Alexander had gone to Botha’s Hill to gain oracular insights, he couldn’t have anticipated what happened next. After Paton had taken his measure of who he later described as the “sober and serious young man”, he asked him if he’d like to take over from him and write the Campbell book. Twenty years later, when Alexander published his biography of Paton, he wrote, “I was so overwhelmed I could hardly speak, though neither he nor I could foresee that he had changed the course of my life decisively.”

***

By 1990, I’d read Alexander’s Campbell biography five times but, as I hadn’t brought it with me, I thought having a copy would be of help in tracing some of Campbell’s footsteps. I drove into town, went to Adams & Co in West Street and asked the shop assistant if they had it in stock. She looked uncertain and said she’d need to go and ask. While she did so, I browsed through some second-hand books and found what still seems to have been a ridiculously underpriced 1905 edition of Bishop Colenso’s Zulu-English Dictionary. When the shop assistant returned, her uncertain expression had changed to a puzzled frown. “Could you tell me”, she asked, “what exactly does Roy Campbell do?”

A multi-storey complex had been built over what was once Campbell’s childhood home on Musgrave Road. I continued up the Berea, then drove along Marriot Road until I came to the Cape Dutch house built by his uncle, Sir Marshall Campbell. This is where his aunt, Killie Campbell, began a collection that grew into what is today the Killie Campbell Africana Library. I sat down at a gleaming wooden table in an air-conditioned room and the librarian gave me their 13 Campbell files.

A visceral connection

There were drafts of poems, postcards and many handwritten letters to Mary. Although I’d read some of these letters in Alexander’s biography, it felt intrusive to be reading the real thing. On the other hand, it helped me feel a visceral connection with the man. I also came across the notebooks that Mary had shown Paton. I found a fragment called “Stones”.

Dead selves upon whose stepping stones I came

With Pegasus, the bugbear of the backers,

A dark outsider, rescued from the knackers

To share the petrifaction of my fame.

It was good to see my title in his handwriting — but now the dark outsider is Pegasus, the winged horse representing speed, strength and artistic inspiration. I also read contemporary newspaper reports of his death and several obituaries. It almost came as a shock, as if I was reading about the death of a friend for the first time.

In December 1924, Campbell made a heroic return to Durban as the archetypal local-boy-makes-good. In London, he’d lived on the fringes of Bohemia, had married the beautiful Mary Garman, and had spent time in a stone cottage in Wales where their daughter Tessa was born and where Campbell completed a book-length poem entitled The Flaming Terrapin. He circulated the poem, TE Lawrence (yes, Lawrence of Arabia) loved it and sent it to Jonathan Cape urging him to publish it, which he did in May 1924. Campbell woke up one morning to discover he was famous.

Unlike today, 100 years ago a poet could be a celebrity. But even then — unless you were Rudyard Kipling — writing poetry wasn’t going to pay the bills. That obviously didn’t occur to Campbell and he convinced Mary that life would be more congenial in Natal. He was also sure he’d be able to earn a living. His father, who’d been bankrolling him up to this point, suggested he take up journalism. That did little to improve relations between father and son.

Campbell eventually found a benefactor — Lewis Reynolds, the wealthy son of a sugar baron — who greatly admired The Flaming Terrapin and set them up on his Umdoni Park estate in a cottage on the beach at Sezela. There they lived a carefree life and Mary later told Alexander she thought they were probably the world’s first hippies.

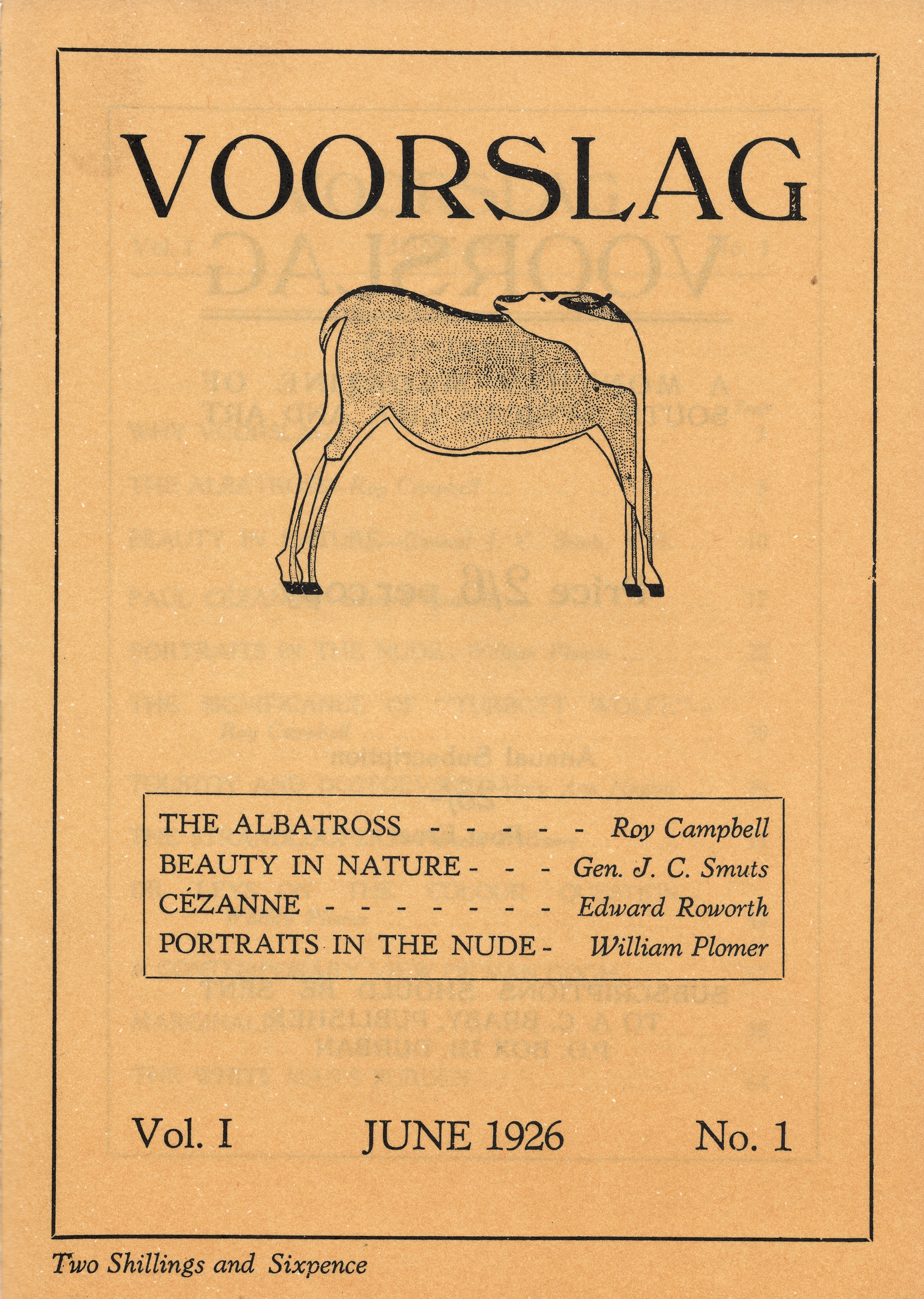

In 1925, Campbell met the young William Plomer who’d just completed his first novel while working behind the counter in his father’s trading store in Entumeni. Campbell greatly admired Turbott Wolfe — which had at its centre a racially mixed marriage — and when Reynolds agreed to finance a literary magazine, Campbell persuaded Plomer to join them at Sezela. The magazine was called Voorslag.

It was Plomer’s suggestion to co-opt the young Laurens van der Post who was working on a Durban newspaper. He came out every weekend and was appointed Afrikaans editor, which made Voorslag the first bilingual literary magazine in the country. Campbell also wanted to get contributions from John Dube so the magazine could become trilingual.

‘Voorslag’. (Image: Supplied)

The appearance of Turbott Wolfe in March 1926 was greeted with howls of indignation in Natal where the consensus was that it was “just not cricket”. Given that Campbell and Plomer wanted to use the magazine to “sting the mental hindquarters of the bovine citizenry of the Union”, it’s unsurprising they didn’t last long as editors.

Period of inspiration

After they’d resigned and before they went their separate ways, they used what time they had left to do their own writing. Alexander maintains it was, “the single most fertile period of inspiration in Campbell’s life”. This is when he wrote some of his best-known poems, which were published in 1930 in Adamastor. His title came from the poet Luís de Camões’ epic The Lusiads (1572).

This Portuguese epic recounts the story of Vasco da Gama’s heroic voyage around The Cape of Storms, and Adamastor — a Titan of Greek mythology created by Camões — had been banished to the Cape by the sea goddess Doris where he made it his business to threaten the Portuguese explorers with “grim disasters”. Campbell had read this poem while in Sezela at the urging of his friend and benefactor CJ Sibbett.

There was much in Camões’ life and work that resonated with Campbell. He lived a bohemian life, apocryphal stories abounded about forbidden love affairs and he was no stranger to the inside of a prison. When he set sail from Lisbon on Palm Sunday 1553, his last words were those of Scipio Africanus: “Ungrateful fatherland, you will not possess my bones.”

I walked along the beach at Sezela. You couldn’t tell where the cottage had once stood but being there made everything feel real. When Dark Outsider was performed, pointing out beyond the breakers — to the back of the stalls — Campbell (Jamie Bartlett) turned to Van der Post (David Clatworthy) and said, “Luís de Camões must have sailed past this beach in 1553. The first poet to write about this country.” Well, certainly the first European poet.

‘Dark Outsider’ by Anthony Akerman. (Image: Supplied by author)

William Plomer (Thomas Hall), Roy Campbell (Jamie Bartlett) and Laurens van der Post (David Clatworthy). Like Campbell, Bartlett died aged 56. (Image: Supplied)

In December 1990, on a visit to London, I went to Bush House and, in the sound archives of the BBC, listened to shellac recordings of Campbell reading from his poems. Unlike his friend Dylan Thomas, he didn’t impress as a performer of his poetry, but I was moved when I listened to his rasping reading from his poem Tristan da Cunha in his rich South African accent. After that, I met up with the novelist Tony Peake in The George for a drink.

The George is a generic English pub Campbell frequented while working as a talks producer for the BBC. In this capacity, he often engaged Thomas to read his poetry on air. Campbell’s superiors at the Third Programme took a dim view when, on one occasion, Thomas passed out in front of the microphone before he’d read a word. Campbell swore blind he’d never let that happen again and so it became his responsibility to keep Thomas sober before a broadcast. One alcoholic persuading another alcoholic that having a drink was not a good idea has all the makings of a vaudeville comic turn.

Tony and I had been students together at Rhodes and I don’t think he had anything more than a passing interest in Roy Campbell, but I was obsessed and told him how this pub had once been the scene of a literary dispute between Campbell and Louis MacNiece — the Mac in MacSpaunday. They traded blows and, on this occasion, it was Campbell who got the bloodied nose. After that, Campbell bought MacNiece a drink, they became the best of friends and ever after he staunchly defended him against any criticism from others. That was Campbell.

Two decisions

Although it wasn’t exactly a New Year’s resolution, at the beginning of 1991 I’d made up my mind about two things: I’d spend six months in South Africa, after which I’d decide whether I’d return permanently — and while I was there, I’d write Dark Outsider. Although I felt ready to start work on the play, I’d been putting off the one thing I knew I still had to do: visit Campbell’s grave in Portugal. Did I think of it as a pilgrimage of sorts? Had Campbell’s Catholicism rubbed off on me? Did I want to go there to ask for his blessing?

But time was running out. I’d never been to Portugal and didn’t feel like going there on my own. Besides, I was flying to Johannesburg on 28 March — and on 22 February my newly found sister Jean arrived to stay with me en route for a gap year in the United States. So it just wasn’t going to happen.

I treasured the quality time Jean and I spent together, enjoyed playing the avuncular role of significantly older brother and proudly showing her off to my friends in Amsterdam. But after she’d decided to extend her stay by two weeks and, quite unexpectedly, I’d had a financial windfall, I asked her if she’d like to spend a long weekend in Portugal.

On our first day, we explored Lisbon’s city centre, then took the ferry across the Tagus to Cacilhas to savour the bacalhau and plan the next day’s expedition. Well, as there wasn’t much planning to do, I ordered another glass of vinho verde and chilled. All we had to do was catch the commuter train to Sintra and, from there, a bus to São Pedro which, according to Alexander’s biography, was near Sintra. The village had a hillside cemetery where Campbell had been buried on 27 April 1957.

The author’s sister Jean in a Lisbon Café. (Image: Supplied by the author)

It was a 10-minute walk from the station into Sintra, but there didn’t seem to be a bus stop for buses going to São Pedro. I asked passers-by in the Spanish I’d picked up while directing a Fugard play in Mexico, supplemented with a smattering of restaurant Italian. From their uncomprehending expressions, I might as well have spoken Afrikaans. But Jean clearly admired my polyglot skills and felt secure in the knowledge that her older brother knew exactly what he was doing.

Leap of faith

I didn’t want to disappoint her and walked around purposefully until I saw a sign pointing in the direction of São Pedro de Penaferrim. Was that the right São Pedro? What if there was more than one? I couldn’t exactly ask anybody, so I decided that, like a true pilgrim, I had to take a leap of faith. I told Jean we’d start walking and that we’d probably find a bus stop along the way. Jean was wearing trainers but, predictably, I was wearing entirely unsuitable white slip-ons.

It always takes so long to get somewhere when you don’t know exactly where you’re going. We kept telling each other we’d probably see it when we turned the next corner. Whenever we encountered a local walking in the opposite direction I’d say, “Bom dia” and, with an interrogative inflection, “São Pedro?” They’d respond with, “Sim, sim” and gesticulate encouragingly in the direction we were going.

By the time we arrived in São Pedro, my feet felt as if they’d already walked the Camino. There were wedding guests milling around in the street. It was Saturday, the mood was festive and they greeted us hospitably. I asked if anyone spoke English and someone volunteered that he spoke “a leedel.” Asking a wedding guest for directions to a cemetery didn’t feel quite right, but he was unfazed, kept repeating the word “cemitério” and pointed to another road leading out of the village.

Campbell’s final resting place. (Image: Google / Supplied by author)

In the next village, which Google Maps informs me is Bairro Alto da Boavista, we asked a woman in an antique shop and she pointed the way up the hill along Rua Luís de Camões and then right into Rua Alto da Bonita where we found the ornate village cemetery. All the graves — mostly of white marble — were well maintained and many were adorned with fresh flowers. There was no one we could ask and, as the graves were not arranged according to any discernible logic, Jean and I split up and walked the length and breadth of the necropolis. We eventually found his grave close to the main gate.

A simple stone cross stands at the head of a granite slab on which his name and dates are carved — as well as the single word that he would have liked to be remembered by: Poet. Below that, added 22 years later after her death, were the words “and his beloved wife Mary”.

I was here, finally.

The grave of Roy and Mary Campbell. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Roy and Mary Campbell’s grave. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Anthony Akerman at Campbell’s grave. (Image: Supplied by the author)

We took photos and looked around. During his 1954 visit, when I like to think I glimpsed him on his way to Botha’s Hill, Campbell extended his stay and, by way of explanation, wrote to Mary saying, “I am longing to see you beloved — but this is the last time I will ever set eyes on my beloved country (How I love it!) so let me take it in all I can before I finish with it.” Before I finish with it. I was sure I’d decide to return home, which made being in his presence on that Portuguese hillside cemetery ineffably sad.

I felt the need to make a gesture of sorts. Although I hadn’t been practical enough to pack a map, I had brought a copy of Adamastor with me. “Buffel’s Kop” is the mountaintop outside Cradock where Olive Schreiner lies buried. I opened the book and read it aloud.

Buffel’s Kop. (Image: Supplied)

On our final day we took the tram to Belém. The tower on the Tagus is where Portuguese sailors departed on their voyages of discovery. It was here that Luís de Camões set sail. Adamastor exacted a severe toll when three of the ships in their fleet were lost at the Cape. Despite the hardships he endured and contrary to his own predictions, Camões died in Lisbon and we visited his grave in the Jerónimos Monastery. In Portugal, published the year he died, Campbell paid the following tribute to Camões: “Once he had written, the Portuguese language was safe for ever.”

Anthony Akerman at the Belem Tower. (Image: Supplied by author)

As I imagined I’d seen Campbell on his way to Botha’s Hill, so he no doubt tried to imagine Camões sailing past Sezela in 1533. It was on that beach one night in 1926, having just completed Tristan da Cunha that he declaimed it – competing with the sound of the crashing breakers – to the young Laurens van der Post. One verse almost prefigured his permanent exile in that hillside cemetery close to São Pedro.

Exiled like you and severed from my race

By the cold ocean of my own disdain,

Do I not freeze in such a wintry space,

Do I not travel through a storm as vast

And rise at times, victorious from the main,

To fly the sunrise at my shattered mast? DM

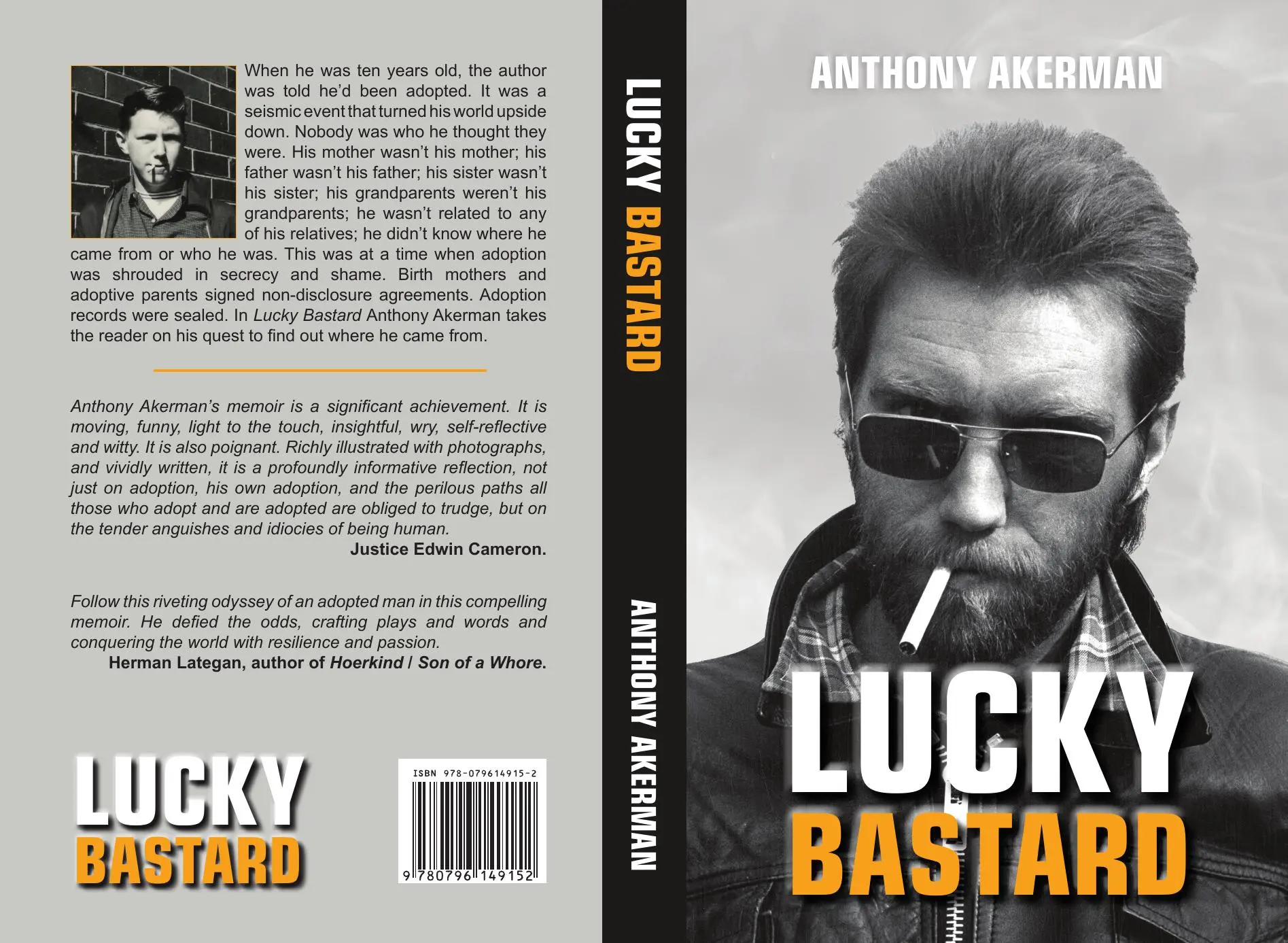

Anthony Akerman’s adoption memoir Lucky Bastard is available at independent bookstores such as Love Books, Bookdealers and Bridge Books in Johannesburg, Clarke’s and The Book Lounge in Cape Town, as well as Ike’s Bookstore in Durban. It’s also available on Takealot, Amazon and Kindle and autographed copies can be ordered directly from the author at: [email protected].

‘Lucky Bastard’ by Anthony Akerman.

Way back in 1961 , faced with ” Horses on the Camargue ” as a Matric set-work in the confines of a particularly po-faced Roman Catholic school , we were certainly ( well at least I was ) unaware of any detail about the Author/Poet. How much easier might it have been to appreciate the magnificent text , had we been aware of some proper account of the man himself. Anthony has filled that gap for me and I am tempted to find that book of poetry again and bask in a contextuality that had eluded me for six decades.

I, too, was led by the poem “Horses on the Camargue” to the the school library where I found a slim Campbell book, “The Flaming Terrapin.” One of my favourite quotes over the years has been

“And Patriotism, Satan’s angry son,

Rasps on the trigger of his rusty gun…”

Then he goes on for an extended passage on, “While pale Corruption…”

A flamboyant style of writing but curiously still relevant today.