Tribute

A personal memoir of my time with Ronnie Govender

Ronnie Govender’s At the Edge was seen by hundreds of thousands over many years. Pat Pillai recalls his time with him in the 80s, and the first staging of this iconic piece of theatre.

“Over my dead body!”

It was the trauma of the government’s final eviction notice that led to the heart attack that killed Thunga, one of the characters in Ronnie Govender’s At the Edge. The play celebrated the vibrant community, and subsequent forced removals, of Cato Manor, Durban. In the play, Thunga refuses to leave his home, uttering the words “over my dead body” when the first eviction orders arrive.

“This is my home. I built it with my own hands. No one is going to take it away from me”. He stayed on, in defiance, when many others had been relocated to Chatsworth.

Ronnie Govender wrote this script more than 30 years ago and that fateful eviction order was dated 29 April 1960.

Last week, on 29 April 2021, Ronnie Govender died.

When I got the news of his death, this extraordinary coincidence immediately came to mind. What followed was an aching sadness for the loss of a man who was my mentor, friend, and became, in our 30-year relationship, a father figure.

At his memorial service in Cape Town on Monday, President Cyril Ramaphosa wrote on behalf of the people of South Africa and extended sincere condolences. He said Dr Ronnie Govender “provided a vibrant and textured addition to the rich tapestry of our national identity” and that he “gave a voice to the oppressed and the marginalised”.

Over the years, hundreds of thousands of people have seen At the Edge around the world – in South Africa, Canada, the UK, India and other countries. At first, it fell to me to tell these stories. (Later, Leeanda Reddy and Jailoshni Naidoo each did so – both very talented storytellers.) However, it all started so quietly, on a sunny day, more than 30 years ago…

It was in the 1980s that I informally, on and off, encountered Ronnie Govender at the University of Durban-Westville. His children, Pat and Pregs, were also studying there.

He often came to watch student and protest theatre on campus.

Those were exciting, extraordinary, difficult days. Madiba and our other leaders were still imprisoned. In the 80s campus life at UDW was politicised and always inspiring. We students enjoyed Ronnie Govender’s audacity. He was writing and travelling the kind of conscientising, liberatory, identity-affirming theatre that the government of the day loathed.

I was a young teacher of English and Drama-in-Education, in my 20s. Ronnie was in his 50s, established in the community as a writer, producer and director. I was in awe.

At the end of our first formal meeting he handed me a thick stack of papers and said: “Have a read. There are four acts. It’s a one-man show and you’ll need to play all the characters.”

I gulped and felt the full weight of the script in my hand.

I read that script through twice that night and by the morning was terrified – but determined. What I had just read was authentic, powerful and relevant. It was funny, human, poignant and heartbreaking – all at once. It was also a story that, at that time, had not been told. It was anti-apartheid theatre that didn’t preach. There was no slogan bashing. It was accessible. This work was profoundly human – and I thought it could transcend the limitations of its time, location and specific context. As a teacher, I thought Ronnie had developed a script that was an entertaining “living lesson” that would restore dignity and validate many.

Later that day I spoke of all this to Ronnie. He listened and when I was done, he smiled his hallmark, naughty side-grin and chuckled.

“Okay then. Let’s get on with it.”

It took just over six weeks, six days a week from 8am to late at night to craft the show. Forty-two characters was crazy, I said – and after much debating we reduced that to 39. Then 36. Ronnie loved each one so much, he couldn’t let them go. But the show was more than three hours long! We had work to do. It had to be a tight, well-crafted two hours.

Each character had to be distinctly portrayed, but the story had to flow seamlessly. I frustrated him. He frustrated me. Some days I asked to be left alone. Some days he went off and came back with four new pages that solved a creative problem – but extended the show by seven minutes! Other days we cut out pages and reduced them to a few lines. Then I performed the revised version for him. There was silence while he considered it. Then, with great certainty he’d say: “That’s it!” or “No! I don’t like it. I’ll rewrite it tonight.”

We worked hard; we laughed lots; we disagreed at times, we moved scenes around. There was symphony and creative tension and we both loved it. I respected his writing, his theatre instincts, his experience and his talent for capturing life on the page.

He respected me as an upstart who wanted to tell the story authentically on the stage.

We always found that common purpose inspiring. When I was unsure, we’d step outside, breathe a little. He could be surprisingly sensitive. He’d lift me up and guide me back. My writer/director was also my teacher. What I learnt in those weeks have stayed with me to this day.

And so it went. Day by day, page by page, character by character being shaped and given voice. It was important to us that, even though we had some dramatic licence, that we tell the stories of the people of Cato Manor honestly and with dignity.

I wasn’t an obvious choice. I grew up in Rylands, Athlone on the Cape Flats. This was a Durban, largely Indian community from the 40s and 50s that he captured in At the Edge. I didn’t know the subtleties. I needed to find the nuance but still maintain the universality and humanity of the story. Ronnie, always good at reading the unsaid, sensed I was stuck. And so, one day, he said: “Cancel rehearsals for the next few days. Tomorrow we’ll take a drive.” The next day, with a stack of sandwiches that his wife, Auntie Kay, packed for us – freshly buttered bread with tin-fish chutney, made with lots of onions and green chilies – he drove us to Cato Manor.

Much of it was in ruins or overgrown, but there was enough left for him to point out the hotspots, the streets and the overgrown plot that once held someone’s wood and iron home; someone he knew. Zinc shacks were now beginning to pop up. “Cato Manor was spontaneous. The beginnings of an integrated community,” he said. “They hated that prospect the most.” I lifted my pencil and pad. My immersive research process had begun…

Later, we stopped under the shade of a tree. Leaned up against the car and spread our tea and sandwiches on the warm bonnet. In that moment Ronnie Govender wasn’t my director. He was a son of Cato Manor. A disenfranchised South African who was marginalised. I asked about his childhood, his parents, his early days as a young man… his activism for non-racial sport, his days as a journalist, his protest theatre, his family. I listened. That day I saw a strong six-foot-two-inches man moved as he spoke of community, life, loss and his dreams for a better South Africa. “If only those in power saw the potential in all our people 50 years ago, he said. Just imagine! But it’s not too late. We’ll soon have a government by the people. It’s close now.”

The next day he took me to meet some of the people he knew from the area. They greeted each other with the warmth and enthusiasm that only old friends could. The years between people can be felt in their lingering smiles and their comfort with silence. Some spoke of his accomplishments. Others, only of their common history. He was far more interested in their common history, curious to know more about so and so…

At a local, well-worn, hops-infused pub, I met some of his brazos. Ordinary men from different walks. They laughed and reminisced, using Tamil phrases and slang that I’d never heard before! I put my spectacles on, made notes and asked for the spelling of some of those words. It’s what us teetotal nerds do, which instantly spoilt the mood. There was a pause while they looked at me in appalled disbelief. “What’s wrong with this lightie, Ronnie? This ou is having a glass of milk and making notes!”

Ronnie put his arm around me and said: “Hey, give the lightie a break. We’re working on a show together. And don’t worry,” he chuckled, “he’s slowly making his way to a milk stout.”

Then he repeated my question for me. Soon I was being regaled and as the dop flowed, I got insights I could never have gained otherwise. Ronnie, too, while reminiscing, was transformed and I saw a different side to him over those days.

***

Being a one-man show, we travelled lightly, and took the show to many communities, visiting small towns in then Natal, Transvaal and the Western Cape. I had no idea that so many small towns existed in our country. From small community halls to one thousand-seater town halls – all were packed. One show per town does that. These were not proper, formal theatres. Ronnie’s son, Daya, joined us sometimes and assisted the team as we all set out the chairs, darkened the windows, set up the two portable lights and two speakers and then, lastly, arranged the simple set on stage. There was much clatter and hurried work to do, and we all got on with it rather efficiently. Ronnie would then cast his eye across the space, give us the thumbs up and signal us to vacate. Silence. We were ready!

I went backstage. Ronnie went front of house. The doors were then opened, and the crowd streamed in rowdily. The energy in the venue was palpable.

At first, no established mainstream theatre wanted the show. One of our early venues, the Cane Growers Hall in Durban, had an occasional rat running over audience members’ feet while I was on stage. After a weird Mexican wave of shrieks across the row, it was not unusual to have audience members tuck their feet under their bums. At the interval, Ronnie checked on me – and said: “Naina, if any rats run across the stage just work it into the show; improvise. There were a few rats in Cato Manor, too, you know.” Then he’d grin and chuckle off. Ronnie had a boyish charm, a mischievous streak, and the intellectual gravitas to hold his own among the best.

His campaign to get At the Edge onto mainstream stages continued and soon we were invited to The Baxter Theatre in Cape Town. Then major arts festivals booked the show. While at the Edinburgh Arts Festival in Scotland, I was unsettled. I couldn’t sleep.

Would this international audience get it?” I wondered. Ronnie, relying on some wisdom from his days in sport, suggested that I run in the morning. “Spend an hour sitting on the park benches. Do some people watching. Then run back,” he said.

“Why?” I asked.

“To get some oxygen, climatise, to shake off the energy and to settle your mind.” So, I ran 5km a day on the streets, parkways and byways around the iconic Edinburgh Castle so that by the end of the day I was calm and ready for the stage. It worked. I also had a sense of my audience, their chatter, and the smell of the city. I did that every day for the duration of the festival, and I didn’t feel unsettled when my audience came to sit on our theatre benches and watch me.

In Edinburgh, At the Edge was staged in the same venue as Dylan Thomas, played by Bob Kingdom and directed by Anthony Hopkins (not yet knighted at that time). In an arts festival, venues are recycled. As we broke set, his show moved in. Our dressing rooms were next to each other, separated by a simple screen. As Hopkins was guiding his actor, Govender was debriefing me. It was surreal. Then came Toronto, then Glasgow, then Johannesburg and so on. In all instances Ronnie and the show received critical acclaim. And when the crowds were gone, Ronnie had his pen – and he could spend hours alone, writing, chuckling with his characters.

Madiba was released in 1990. This time, on our travels, I watched as Ronnie Govender stood tall and told the world that South Africa was wide awake at the dawn of democracy.

It was a quiet privilege for Ronnie when, a few years later, he and I presented At the Edge for our first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, at a packed Playhouse Theatre in Durban.

Yes. Ronnie Govender – he’s that boy who grew up in Cato Manor. He’s the man who beat the odds, who beat the system, who had the street smarts, the creative talent and the intellect to take his stories around South Africa and the world – and helped give this boy a break in life.

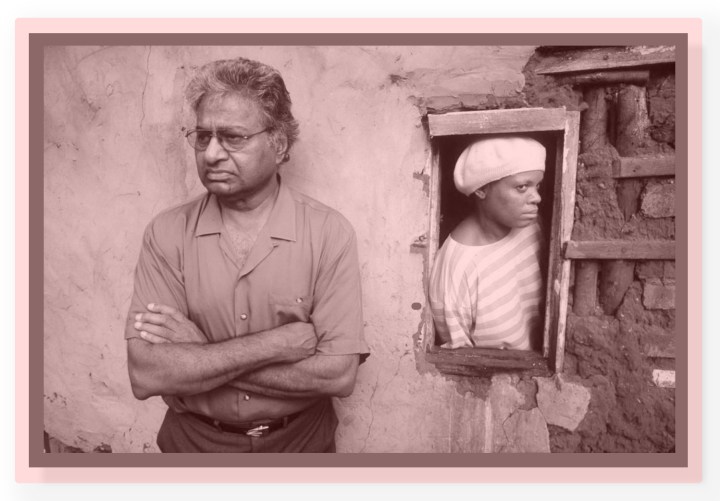

Pat Pillay and Ronnie Govender, 2018

***

I will miss you, Uncle Ronnie. Romba nandri. Thank you.

Leaving us on 29 April is perhaps another sign of how fate bows to your pen.

Rest in peace. Your body of work lives on… Always. DM/ML/MC

Dr Sathiseelan Gurilingam ‘Ronnie’ Govender (16 May 1934 – 29 April 2021). From 1962 onward Govender wrote, directed and produced many award-winning plays, among them The Lahnee’s Pleasure, 1949 and Beyond Calvary; At the Edge won the 1997 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for best first book, Africa. Govender received the government of South Africa’s Order of Ikhamanga in 2008 for his contributions to democracy, peace and justice in the country through theatre. In 2014, DUT awarded Govender an honorary doctorate. From 1991 to 2008 Govender published seven books/anthologies.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.