ANCIENT JOURNEYS

Florence Baker: The slave who braved all for love

The Wikipedia entry says it all: ‘Florence Barbara Maria Szász, an orphan who became a slave, explored the Nile and died a lady.’ If Hollywood had been around in the 19th Century, her life would have made a blockbuster.

Very few people who visited the gracious home of Sir Samuel and Lady Florence Baker in Sandford Orleigh, Devon, knew of their wild adventures and enduring love affair that began as they locked eyes at a slave auction in Vidin, Bulgaria, in 1859.

Florence was born in Transylvania and travelled with her soldier-father during the Hungarian revolution. After the defeat of his army, most of her family were murdered by Vlad peasants. She was sent to a refugee camp in Vidin where she was kidnapped and sold to Armenians to be raised in a harem. For the next few years, pampered, educated and treated kindly, she did not realise she was being groomed as a slave until auction day.

What happened in the Vidin slave market comes right out of the Arabian Nights. Just 14, beautiful, blue-eyed and dumb with outrage, she was astonished to see Baker, who’d attended the auction as an afterthought, aggressively bidding for her against the Pasha of Vidin, who eventually paid the higher price.

Baker, a wealthy young British landowner and big-game hunter, bribed the eunuch in charge of Szász, abducted the girl and fled Vidin for Bucharest, pursued by the enraged Pasha.

Bored with commercial life, Baker planned to explore the Nile and took the girl along. Proficient in Arabic, Turkish, German and Romanian, she’d be useful, he reckoned. It turns out she was much more than useful. Pretty soon Samuel fell head over heels in love with her.

***

The journey up the Nile would involve hardship, illness and near death. But in the end, it would be a love affair that would endure through more dangers and challenges than any pampered Victorian lady could imagine.

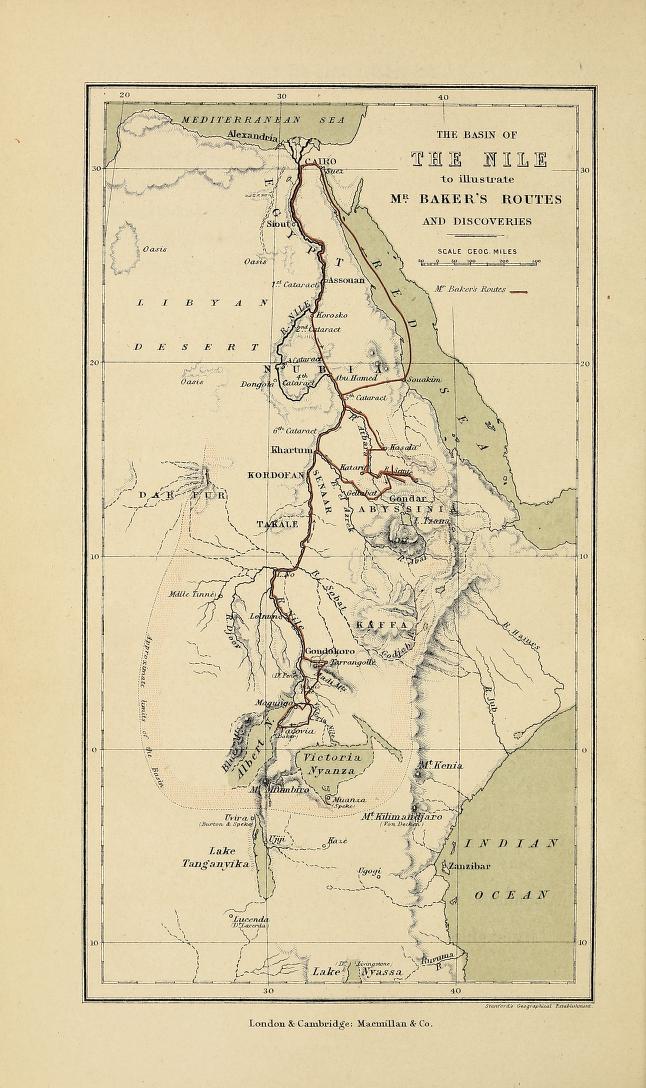

In 1861 they secretly set off to discover the source of the Nile. “I had not the presumption to publish my intention,” Samuel wrote, “as the sources of the Nile had hitherto defied all explorers. But I had inwardly determined to accomplish this difficult task or die in the attempt.”

But what about Florence? “Had I been alone,” he wrote, “it would have been no hard lot to die. But there was one who, although my greatest comfort, was also my greatest care, one whose life yet dawned at so early an age that womanhood was still a future. I shuddered at the prospect for her, should she be left alone in savage lands at my death.”

Samuel tried to dissuade Florence from accompanying him. But the girl refused to be parted from her saviour.

They sailed up the Nile for 26 days, then set off on camels across the Nubian Desert which was “like waves on a stormy sea that had turned to stone.” After two days they reached an oasis surrounded by the skeletons of camels “which had gasped their last with no worms to devour their carcasses.”

Thirteen days of waterless desert later they reached Berber where Florence proved her worth as an Arabic translator. They trekked up the river into the area of the Sudd floodplains where Florence came down with fever, which finally “yielded to quinine” when they reached the town of Crassula which, to their surprise, had a governor and a doctor. They pressed on up the Atbara River (in reality the Blue Nile).

Samuel’s imposing stature and Florence’s engaging beauty served them well in meeting the Berber people who held both in esteem. Samuel’s descriptions of nomadic life were later to win him praise and membership of the Royal Geographic Society.

The Bakers reached Sofi (in present-day Ethiopia) and found it so pleasant they decided to stay for three months to wait out the rainy season, setting up “as pretty a camp as Robinson Crusoe himself could have coveted.” They rested and, reading between the lines of Samuel’s journal, made love.

That ended when Florence contracted gastric fever then boils, the latter which Samuel cured with gunpowder and sulphur “which I had found successful with mange in dogs.”

Having correctly assessed that the source of the Blue Nile was the Abyssinian highlands (it’s Lake Tana), they returned to Khartoum to rest and recover, then set off again up the White Nile. The explorer John Speke had established its source was Lake Victoria, but what lay between it and Khartoum?

At Gondokoro, Florence, though fiery by nature, tapped into her considerable diplomatic skills for which Samuel had no patience and kept the expedition intact and moving forward, despite a mutiny among the bearers. The couple fed off each other’s adventurous spirit and were stronger together than alone.

A sheikh they met was amazed by Florence. “Look at your wife,” he said, “she has travelled with you far away from her own country and her heart is stronger than a man’s. She is afraid of nothing.” When she let down her long blonde hair, Arab women crowded around to marvel. She refused to sit side-saddle and wore trousers.

Often the couple would ride ahead of the camels and sleep curled up together under the stars waiting for them to catch up, using gun stocks as pillows.

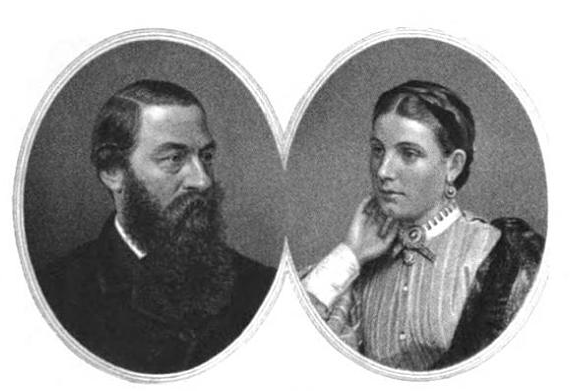

Florence and Samuel White Baker as illustrated in a book of 1890 (Image supplied)

Progress up the White Nile was slow, bug-infested, malarial and dangerous. Much of the team eventually abandoned the Bakers. Deep into Equatoria, a slave catcher demanded Florence in return for free passage. Samuel held a gun to his chest until he relented and let them pass.

Almost within sight of a lake, that Samuel named after Prince Albert, Florence got sunstroke and became insensible, near death. Samuel stayed at her side for seven days without sleeping, holding her hand. He was about to order her grave to be dug when she opened her eyes and began to recover.

Both of them, weak with fever, finally stepped onto the beach of the lake, then continued upriver to behold a massive waterfall that Samuel would name after Sir Roderick Murchison of the Royal Geographic Society.

The trip back to Khartoum was hellish but they made it, though they had been given up for dead.

“The past appeared like a dream,” Samuel wrote as they entered the town. “The rushing sound of the train renewed ideas of civilization. Had I really come from the Nile sources?

“It was no dream. A witness sat before me — a face still young, but bronzed like an Arab by years of exposure to a burning sun, haggard and worn with toil and sickness and shaded with cares happily now past, the devoted companion of my pilgrimage, to whom I owed success and life – my wife.”

They returned to England where Samuel was given a knighthood and Florence, after a formal marriage, became Lady Baker. Samuel bought a stately home in Devon where they lived long and happy lives devoted to each other. However, Queen Victoria, discovering that Samuel had been intimate with Florence before marriage, forever excluded his wife from Court.

Lady Florence Baker (1841 – 1916), the wife of explorer Sam Baker, circa 1865. Born Florence von Sass in eastern Europe, she was rescued from an Ottoman slave market by Baker, who took her on his African travels before returning to England to marry her. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Florence survived Samuel by 20 years and became known for her graciousness and generosity until the day she died, the perfect Victorian lady. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What an intriguing story, beautifully written.