Maverick Citizen Op-Ed

Covid-19 exposure notification apps: We have most of the technology – we just need the trust

South Africa should consider joining a growing list of countries using or developing smartphone apps that warn users of possible exposure to Covid-19.

South Africa is currently facing the fourth-largest outbreak of Covid-19 in the world, behind only the United States, India and Brazil. In response, the South African government has pursued a number of public policies to contain the disease, including mandating the wearing of masks in public and suspending certain sectors of the economy.

Most importantly, South Africa has significantly increased its Covid-19 testing capacity, going from about 5,000 tests per day in mid-June to about 45,000 per day at present.

However, there is one policy intervention that South Africa has not yet adopted: using smartphones to warn citizens about possible exposure to Covid-19. About 60% of South Africans are smartphone users, and could potentially benefit from such a system.

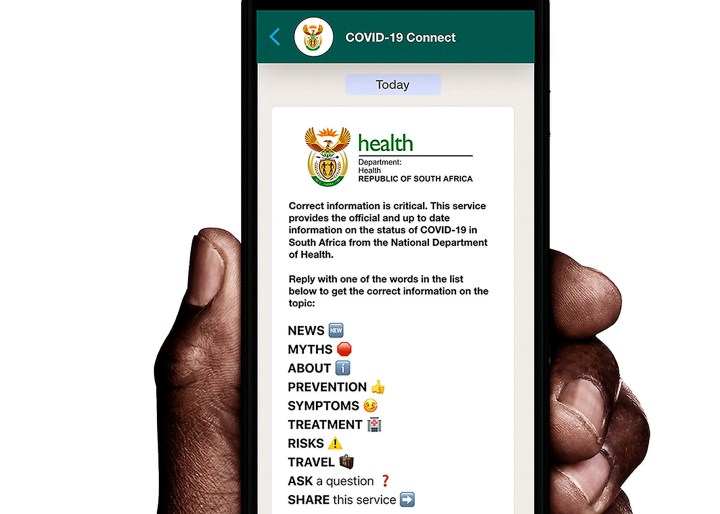

Several other countries have already released “exposure notification” apps, or are currently developing them, including Kenya, Germany, Brazil, Austria, Japan, Mexico, Uruguay, and the Philippines. South Africa should consider joining this list.

Here is how such a system would work. You would visit the app store on your smartphone, and download an official exposure notification app, which would be published by the South African government. Once installed, the app would not track your location. However, it would use your phone’s Bluetooth antennae to keep track of nearby devices, and would store this information in the form of anonymised tokens.

If you come into close proximity with someone who later tests positive for Covid-19, you would receive a notification on your phone. This message might say something like:

“Three days ago, you were near someone who has shared their positive diagnosis of Covid-19.”

You would then be encouraged to get tested for Covid-19 yourself, or to simply self-isolate in order to decrease the possibility of infecting your family and co-workers.

Can it be built?

Such a system might seem expensive and complex to develop, prohibitively so, perhaps, in a resource-constrained country such as South Africa. However, most of the underlying technology has already been developed and deployed.

In fact, if you’re reading this article on the internet, you probably own a smartphone that is capable of receiving Covid-19 exposure warnings. You can test this, if you have an Android smartphone, by tapping on “Settings” and “Google”. If you have an iPhone, you can tap on “Settings”, “Privacy”, and “Health”. You should then see an option for “Covid-19 exposure notifications”. However, you won’t be able to turn these notifications on. This would require a user-facing exposure notification app, which would have to be released by the South African government.

The technology that enables this is an application programming interface, or API, that was jointly developed by Apple and Google. An API is a set of tools that developers can use when creating an app, which allows different pieces of software to communicate with each other. Due to the privacy-sensitive nature of this particular API, however, most software developers are unable to make use of it. Only governments, and officially recognised public health authorities, can tap into the exposure notification API. (It should be noted that the South African government has released an identity verification app called Covi-ID, which does not provide exposure notifications.)

Privacy fears

Would an exposure notification app threaten the privacy of South Africans who use it? For many people, the idea of installing a government-created “tracking app” on their phone – especially one that asks for sensitive medical information – inspires a visceral sense of horror. This is not an unreasonable fear. Governments and technology companies alike have engaged in blatant violations of online privacy in the past, as demonstrated by events such the Edward Snowden leaks and the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

However, in the case of the exposure notification API, these fears are largely misplaced. The API was designed to protect personal privacy, and most cybersecurity experts and online privacy advocates who have studied it have been impressed with the lengths to which it goes to achieve this. The API uses Bluetooth rather than location data; the tokens are anonymised and contain no personally identifying information; the system as a whole is opt-in at every stage.

The API does not require users to share their Covid-19 status with Google or Apple; instead, these records are stored by the same public health authorities that administer the tests. While no system is perfect, it’s very difficult to see how this particular API could be used as a spying tool.

If more people are taking an interest in how their online activity is being tracked and monetised, this is, on balance, a good thing. However, most of the objections to the exposure notification API are based on misunderstandings and vague fears, rather than specific objections to the API’s security architecture.

It would be unfortunate if we allowed paranoia over an illusory threat to deprive us of a tool that could be usefully employed against the genuine threat of Covid-19.

Would it work?

Would exposure notification be an effective public health intervention? This is a difficult question to answer, in part because the evidence from other countries is still very limited. The API has been available for governments to use since 20 June. Over the past month, 18 countries have rolled out exposure notification apps, but it remains to be seen whether these apps will be widely adopted and whether they will have a measurable impact on the disease.

Of course, a smartphone app will have little impact on its own, regardless of how well-designed or sophisticated it is. For the app to be effective, members of the public first need to install it, and they need to trust its privacy model enough to share a positive test result if they receive one. This is not merely a technological problem, and any solution will likely require insights from psychologists and social scientists.

Furthermore, exposure notification can only work in the context of widespread and accessible Covid-19 testing. South Africa has already increased its testing capacity significantly, but there is clearly more work to be done here.

Perhaps the strongest argument in favour of exposure notification is this: it would be a low-risk policy intervention that would not cause any harm, and would have the potential to be a valuable resource. It would not endanger the personal privacy of South Africans, and it would complement other public health interventions rather than compete with them. By steering people towards testing when they’re more likely to be at risk, the app could help South Africa to increase the efficiency of its testing efforts.

And by stopping lines of infection before they can spread, it could help to free up scarce medical resources for people who have the greatest need of them. This seems like an intervention worth trying. DM/MC

Laurence Caromba is a senior lecturer in International Studies at the Independent Institute of Education. His research interests are foreign policy and technology. He writes in his private capacity.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider