ANALYSIS

Cosatu’s great Eskom bailout plan — a critique

Cosatu’s proposal to use government pension funds and development bank finance to slice Eskom’s debt in half is gaining traction and has conditional approval from President Cyril Ramaphosa and government as well as, surprisingly, some support from business. Yet the proposed bailout raises the issues of moral hazard and is more vulnerable to a considered critique than has been presented so far.

The idea of using government pension fund savings to bail out Eskom has enormous superficial appeal, but there are three reasons why the government should not go this route.

First, there is the issue of sequencing, or, to put it another way, do we actually know what Eskom’s financial requirements will be over the next five years?

In its most recent financial results, Eskom painted its financial position as dire. But it’s worth remembering that Eskom has an enormous incentive to present its financial position in the worst possible light because the principal determinant of its income is not really the customer, but the regulator Nersa.

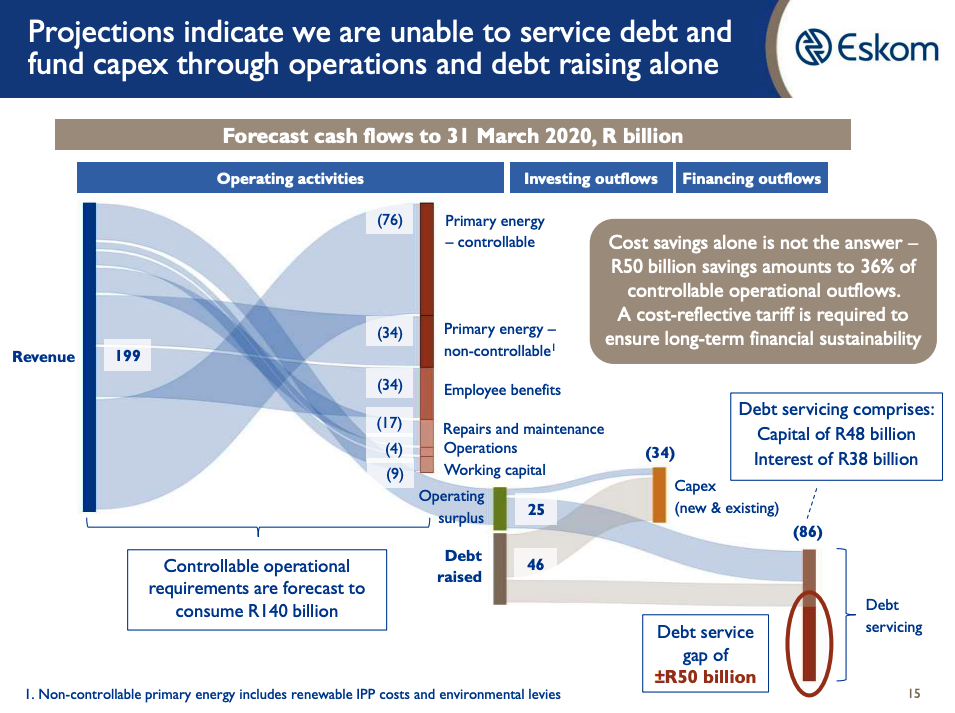

Technically the position is this, according to Eskom: projecting forward to March 2020, the utility will have an income of just under R200-billion and an operating surplus of R25-billion. It will spend about R34-billion over the year on capex, and, it claims, it has debt servicing costs of R86-billion.

That consists of a capital cost of R48-billion and an interest bill on its R450-billion in accumulated debt of R38-billion. With R46-billion in debt raised, there is a R50-billion debt service shortfall, Eskom says. This is why the government has jumped in and granted Eskom about R150-billion in funding support over the next decade.

To me, the question here is this: if that is true, what kind of crazy-assed loans has Eskom been signing? At say, 9% interest, R450-billion debt should demand about R40-billion a year, not R90-billion. This smells of smoke and mirrors.

But there is another question too: the big financial drain on Eskom has been, as everybody knows, its three massive capex projects; Madupi, Kusile and Ingula pumped storage scheme. Technically, these projects are either complete or close to being so. Of course, there will be more capex required down the line, but the problem is we just don’t know how much.

Please, praise to the old gods and the new, it must be at least conceivable that the capex will decline. Madupi and Kusile have cost about three times more than initially planned, but surely at some point that comes to an end.

The thing about the state of Eskom’s finances is that it is almost entirely dependent on electricity tariff increases. Eskom could be effectively bankrupt, which is pretty close to what the utility is currently arguing. Or, its debt could be entirely within its capacity to maintain with governments help. We just don’t know, and until we do, slashing its debt seems more like a Christmas present than a strategy.

The second reason to question Cosatu’s proposal is the state of the government pension fund itself. The point which Cosatu makes about the state pension funds, mainly the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF) managed mainly by the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), is that they are defined benefit funds.

Well, great… for them. That means any shortfall in the fund will have to be picked up by the government — that is, taxpayers. But how likely is that to happen?

Here we enter the rarified world of actuarial science, one of the most complex areas of financial analysis. The facts as we know them are these: the PIC’s funds under management amount to about R2.1-trillion. That seems like a huge pot of cash; surely they wouldn’t miss a couple of hundred billion?

The problem is, they would. According to figures cited by financial advisory firm Intellidex in its presentation to the Mpati Commission, the GEPF has assets of about R1.8-trillion. The estimated present value of future liabilities covered by the assets range from 108.3% to 75.5%.

That’s a pretty big gap. In other words, it’s either in surplus to the tune of R144-billion or it’s R450-billion short. Why is that gap so big? Because you have to factor in a whole bunch of unknowns such as mortality rates, the quantum of final salary, size of the workforce and so on. Consequently, actuaries have come up with a “best estimate basis” (108%) and a “stricter liability measure” (75%).

The important thing to remember here is that the actuarial surplus is essentially dependent on the state of the stock market. Like almost all pension funds, the key driver is JSE because their biggest investments sit in listed equities.

At the moment, the state of global stock markets is glorious. Stock valuations on the S&P 500 are currently sitting on about 25-times their annual earnings. That is massive, and outside of recessions when earnings dry up, it’s almost unprecedented. In SA, the comparative figure is 17 – more modest and close to its decade average. The point is that generally speaking, market valuations internationally are good at the moment and a 5% drop would surprise no-one. That would almost wipe out the actuarial surplus pretty quick which is why defined benefit pensions funds like to build in a bit of a surplus.

And, by the way, practically all the immediate metrics of the GEPF and the PIC are pointing the wrong direction. In 2013 and 2014, the fund’s payouts were almost equal to its investment gains. Fabulous! Hence, all contributions were just bulking up the fund.

But in 2015, this all turned around. For example, in 2018, its investment income was R72-billion, but its payouts were R95-billion.

The point is that even on the “best estimate basis”, taking R250-billion out of the fund would be larger than its current surplus. Cosatu’s idea would fundamentally weaken the retirement funding of its own members because even if the current batch of retirees would be protected by being part of a defined benefits arrangement, the government can only afford so much, and would be effectively forced to cut back on the fund which it could do simply by, say, increasing tax.

The third, and arguably the most important, argument against Cosatu’s proposal is also the most nebulous: moral hazard.

In South Africa, we seem to live in a country without any real accountability. This started years ago when the perpetrators of apartheid killings suffered little or no consequence for what they did. More broadly, the same could be said of the perpetrators of apartheid generally.

And then, along the way, the same standard seemed to be applied to successive wrong-doers, starting with Schabir Shaik all the way to the Gupta family. It’s just soul-destroying.

Letting Eskom off the hook with a huge bonsela just strikes me as an invitation to every government department to sting the government pension fund whenever it messes up, which let’s face it, has been often. Implicitly, the idea is to let future generations pick up the cost. It sticks in your craw, or it does in mine. Once this is done, what’s to stop it happening again. And again.

There are some great aspects of the Cosatu proposal, including the desire to add some muscle to moving away from fossil fuels. But a lot of it is a contradictory mess. Cosatu wants a more sustainable future, but is against losing coal-sector jobs, for example. I’m afraid, on that one, you have to choose.

Cosatu argues this proposal is just like the PIC helping out Edcon to save jobs. There are similarities, but the problem is the quantum is so different. The PIC invested R1.2-billion in Edcon, not two hundred times that.

And it’s worth noting that business’s motives are questionable too: raiding the government pension fund and paying off Eskom’s debt will substantially improve the quality of the loan books of banks, even though they have been avoiding Eskom debt recently.

Several commentators have given Cosatu’s idea partial or conditional support, like insisting that the pension fund’s integrity should not be compromised, as if that were possible.

One fund manager I spoke to had a different idea: approve the idea as long as Cosatu agrees to the GEPF becoming a defined contribution fund, like almost every private-sector fund has done over the past two decades. Then it would be their money they are spraying about so liberally.

Bet they wouldn’t agree to that. BM

Eskom’s total debt was originally misreported in this article. Apologies for the error.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider