BOOK EXTRACT

A slice of learning from the cake of Kaokoveld culture

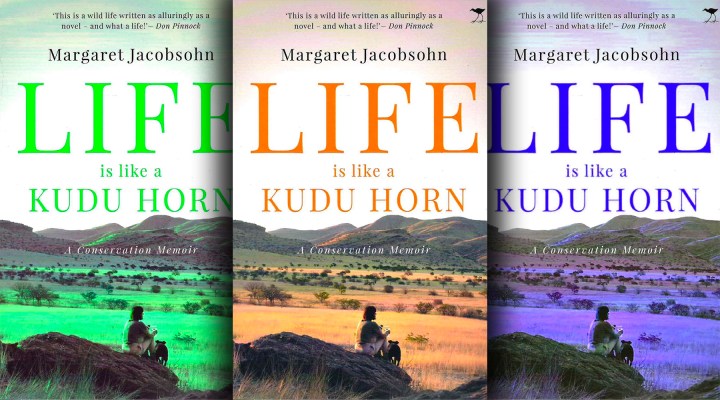

For the past three decades, Dr Margaret Jacobsohn, a self-confessed Western, sedentary, city-dwelling, alienated capitalist, post-feminist, white-skinned, southern African woman, has been living and working among the Himba and Herero people of north-western Namibia. This is an extract from her seminal book on community-based wildlife conservation, Life Is Like a Kudu Horn, published by Jacana.

Living with a remote community of semi-nomadic herders in north-western Namibia in the mid-1980s, hundreds of kilometres from a telephone or supermarket, could be expected to have some tough moments for a researcher from the city. There were – but often not what I expected.

Extended periods without city amenities didn’t worry me as I had done some rough camping over the years. My mind, in those days, was on “higher” academic concerns. Fieldwork tends to teach one as much about oneself and one’s own biases – world “filters” – as the subject one is studying. So for a Western, sedentary, city-dwelling, alienated capitalist, post-feminist, white-skinned, southern African woman there would be issues needing to be unpacked as I engaged with my Himba and Herero hosts who were among the most “traditional” of southern African people.

For a start, the word “traditional” was a minefield in the ’80s: To the layman, even today, and to earlier schools of anthropology, the opposite of “traditional” is “modern”. As a brand new University of Cape Town honours graduate, I knew better. They are not opposites and you could be both at the same time, or different degrees of either at different times. The thrust of my study was to try to understand social relations – between age groups, between men and women, between people and the natural environment – as both reflected by and produced by the eclectic mix of traditional and modern (mass-produced) material culture in use by a group of Himba households. And how these relations were changing.

The idea that the material items that facilitate our lives are active in changing our behaviour and our relationships was a fairly esoteric archaeological concern in those days. My approach stressed human agency – people’s intent – but I also aimed to show just how powerful our material culture and technology is. Even today, you still hear people claiming that material goods are somehow neutral, merely tools to be used by people for either good or bad, as if mere access to them does not change our behaviour in radical and unplanned ways. Who could have imagined where mobile phones would take us? Unrelenting 24/7 connection, all-pervasive social media, cyber-bullying, fake news, election influencing, a new type of war, as well as much that is positive.

We are amazed by near sentient robots and discuss artificial intelligence as a research construct yet we are constantly steered into unintended new behaviour patterns by our smart technical goods. The ghost has always been in the machine.

It was there in the very first tool – no doubt a baby-carrying sling or a woven grass basket to carry veld food, made by a woman, obviously not preserved in the archaeological record. That ghost was also in the second tool – a multi-purpose stone Acheulian hand axe made by Homo erectus man to scavenge and break open marrow bones from a predator’s kill – or to bash in a rival’s head. The point being, he would have been a lot less belligerent without a big lump of specially shaped stone clutched in the hand behind his back.

Another hot potato was culture. Anthropological reading had equipped me with the concept of culture as a large cake, or a round of cheese. Different peoples across the world merely used different parts of the cake/cheese, meaning the term “culture” could never be plural. So there is no such thing as different cultures, just human culture: an Inuit takes his slice from one side; a Welshman or Swedish or Himba person accesses the same cake from a different position and therefore cuts a different portion. Men and women, different age groups, all use and activate their pieces of this cultural confection slightly differently.

And to make it more complicated, culture is not static. It constantly changes, or rather is changed by its users – and by their access to changing technology, for their own socially strategic needs. So, the part of the cultural cheese you are using might have started out as cheddar, say, but over time it evolves into Stilton, or Gouda or mozzarella cheese.

At least that’s how I envisaged it in 1987, driving my second-hand Toyota 4×4 truck along the rutted 100km track between Sesfontein and Puros that took up to four hours to do back then.

I’d tried to explain this cultural cheese concept to a Namibian radio interviewer, Sharon Montgomery, as I passed through Windhoek on my way to the north-west to start my PhD research. Eager to cram everything I wanted to say into the five-minute interview, I’d got a bit intense and I winced as I remembered the expression on Sharon’s face when we got to the big cheese part.

The point about the old “noble savage” syndrome had come across better – or so I thought. People such as the Himba, in their ochre and calf skins, are often seen not as real people but as symbols of whatever the outsider wishes them to be – usually, in the case of Westerners, as exotic, ancient (and very photogenic) people from an idealised old African or even Stone Age past.

Not having the sense to stop while I was ahead, I’d gone on to tell the bemused interviewer that doing research about people was a political and social act that impacts on how people view and assess their own and others’ social status and worth. She’d stopped me there. Time up. Before I could explain that writing down oral histories and telling people’s stories had consequences, that the image of the people constructed by the researcher could be used – or manipulated – by others, including politicians. So sadly, the latter pretentious (but true) pearl of second-hand academic knowledge was never conveyed to the Namibian radio-listening public, assuming they hadn’t changed stations by then.

Around noon, we stopped to give my dog, RDM (Rand Daily Mail), water. RDM, my young temporary translator, the teenage schoolboy John K Kasaona, and I climbed a hill to a shallow cave that begged archaeological investigation. Dassie droppings and a single rusted Coke can. But the view was worth the exertion. Below, a half hemisphere of sapphire sky, low hills wore a sparse cover of tawny-lion-coloured grass. Beyond the hills, pale ochre plains unrolled towards the stark mauve mountain ranges of the Hoanib River canyon.

In the shade of the rock overhang, we ate cheese sandwiches (cheddar!), and I pondered the months ahead: Research could never be objective or neutral; it always reflected the researcher’s own biases and particular social, economic and political theories. The concept of “participant observer”, the term then frequently used by anthropological researchers to describe themselves in their studies, was a cop-out, I’d already decided. My research proposal threw down a gauntlet that envisaged full emotional and intellectual engagement with my host community. I would lay out my “filters” (my piece of cultural cheese was Western, female, sedentary, capitalist-raised etc.) and let each reader of my thesis make of it what s/he will.

Work I’d already done in the north-west the year before for my honours degree had convinced me that Himba and Herero knowledge systems, when allowed to stand on their own terms, were in some ways irreconcilable with Western academic imperatives. However, as my proposal had concluded pompously, this was no reason not to try to hear the Other or to allow academic epistemological jitters to stall attempts to affirm alternative interpretive logics. (I did actually write these words or something similar!)

Within hours we were at Puros, trying to put up my tent in a howling south-west wind under an annaboom tree on the banks of the Hoarusib River’s mostly dry bed. Everything, including John, me and the dog, was soon coated in powdery dust that swirled around in hot gusts of wind. John sensibly accepted an invitation to put his bedding in an empty hut in the nearby village.

The Hoarusib flows just a few days or, at most, a few weeks a year in the rainy season. But near Puros in a few places water rises continuously from linear oases, enabling people, domestic stock and wildlife to survive. Cattle and goats were not expected to remain at this permanent water source all year round; with the rains, the stock was moved out, into the hills and plains, taking advantage of temporary or seasonal waters and grass.

Here was yet another popular myth, that the Himba and Herero people wandered round the north-west randomly seeking pasture and water, when in fact, their success as herders was the result of careful planning and the practice of collectively reserving pasture near permanent water for the late dry season when there were no other options. Grass, and not just water, was the key. After all, in a typical drought, animals die not of thirst but of starvation.

By evening, I’d lost count of the number of mugs of tea or coffee that my camp kettle had produced. Kaupiti Tjipomba, also known as Maria, a smart young woman who had some Western schooling and spoke a little Afrikaans, reinstated herself as my second translator. I was relieved and delighted to see her as I knew there were issues that women would not talk about in front of men or even teenage boys. A stream of people who remembered me from the year before came to greet me. There was news to exchange. Another lineage had moved in because of the war to the north. People were planning to move out of Puros to temporary stock camps any day now so I had come back just in time. It had already rained to the north-east but not enough.

Maria’s father, the old man called Wild Fig (Omukuyu) pointed at distant clouds in the east and said that maybe I’d brought the rain with me. And had my family acquired any cattle yet? Not even goats or sheep? He shook his head sadly.

Tukupoli, his wife and Maria’s mother, who always wore a Herero big dress, wide full-length skirts brushing the ground, even though Omukuyu dressed as a Himba, reminded me I’d promised to bring her some material. Had I remembered? I had but hadn’t unpacked it yet. She said she’d come back tomorrow. Tukopoli’s everyday dress was made from different pieces of materials, their patterns and colours artfully combined. But what she yearned for was a dress made from the same material and this was what I’d brought her: 12 metres of a bold royal blueprint that she would wear for special occasions for many years to come.

Nowadays, the big Herero dress is only seen on older women or only on ceremonial occasions such as funerals or celebrations. But in the ’80s and ’90s in Puros the Herero dress was the daily attire for all women from the Herero lineages living there. Their colourful full-length and full-skirted dresses, gathered under the breasts, are an adaptation of dresses worn by missionaries’ wives in South West Africa at the turn of the century. An extract from one of my field books:

Komiho and Kwatherendu are hard at work picking mealies in the furrow irrigated gardens in the bed of the Hoarusib River. The women talk and laugh – friends and neighbours, the two widows are omuhoko (matrilineally related), having been born into the same eanda (matriclan). The bold red and blue full-length floral dress worn by Komiho makes an eye-catching contrast with the lush, green, chest-high mealie plants. Her graceful Mother Hubbard-style Herero dress is made from up to 12 metres of material. Under its wide skirt, despite the heat, she wears five gathered petticoats.

Her Himba companion Kwatherendu presents a colourful contrast of a different kind: her bare upper body, arms, face and hair gleam red from the powered ochre, mixed with butter fat and aromatic herbs which she smeared onto herself that morning. Her short, pleated calfskin front apron is also ochre-red while the more elaborate back skirt is of soft black calfskin.

On that first evening back John barely left my side. As soon as one group left, another arrived and he was needed to enable us to communicate. Today John is Executive Director of IRDNC (Ed: The NGO, Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation). I like to think that his several stints with me in the Kaokoveld contributed to the values-driven route he chose for his life. Eventually, I fell into my bedroll, dusty and exhausted but happy, having just said goodnight to the 12 Himba men and women who’d shared our dinner of rice and tinned stew. There were no car fridges yet so you carried tins and packets. My mind teemed with information and ideas. I kept sitting up, switching on my torch to make notes in my field book, afraid I’d forget by the morning.

The next morning Puros was transformed. The hot, gritty wind had emptied its lungs in the night, leaving the air still and clear. Slanted rays of morning sun painted the sand plains in shades of apricot. The Hoarusib river bed green-snaked through the middle of the vast hill-fringed bowl that is Puros valley. We walked the 100 metres to the nearest homestead. Sitting on a stone on the sand, outside the cattle-dung plastered dwelling, I started picking up where I’d left off the year before. It was wonderful: everything was interesting to me and people were welcoming. A researcher, especially a woman, was still a rarity so I was as interesting to them.

The days flew by, full and rich. I filled up one notebook, then another. Most people were intrigued by what I was doing and liked the idea that their ways and ideas were being recorded. Very few Himba children went to school in those days. The nearest school was more than 100 kilometres from Puros and children would, therefore, have to stay in the overcrowded hostel during term time.

This meant the family lost youthful labour which was simply essential for a subsistence herding economy.

But many parents believed that their younger children, or at least their children’s children, would and should learn how to read and write, and that therefore they would be able to know their grandparents through my work, a pleasing idea to most.

“Tjanga, write that down,” I was frequently reminded if I was slow to make notes during a conversation.

As fast as the days passed, so my food supply dwindled. I had come supplied, I thought, for about two months. Then I planned to drive the 700 kilometres to Swakopmund to stock up and sort out my preliminary data. On a tight research grant, I didn’t have money to spare. Naturally, I’d brought several emergency bags of maize meal, some powdered soups, an extra 10kg of sugar, plenty of tea and a large box containing 24 packets of biscuits. After two weeks with all my visitors, even my extra sugar and tea was fast running out. My main food supply – tins, rice, pasta and various dried foods – was also uncomfortably low by then. I had not expected to be cooking dinner every night for anything up to 10 or 12 people.

My academic reading was no help in the situation: I felt like a frantic suburban housewife trying to cater for a large number of unexpected guests. I stopped enjoying the social evenings and started feeling anxious and even resentful when people strolled into my camp just before my dinner time, and sat down at my fire. I tried delaying dinner, hoping people would leave but my own hunger usually forced me to prepare a meal eventually. Or John, also hungry, would put on the water for the pap or rice. In this part of the world it was the height of bad manners to eat in front of people without sharing, so share I did, cutting down on the generous portions I had first served.

I expressed my concerns about our food shortages to John but got a noncommittal, typical teenage shrug. It seemed I would have to do something about the situation myself. I felt petty and mean to begrudge my informants a plate of food – after all, I was going to obtain a doctorate from what I was learning here. Nevertheless, as fears of hunger or cutting short my research trip loomed, I steeled myself to speak about this to the people who assembled in my camp each evening.

After a skimpy dinner for 10 – maize meal, bully beef and my last onion – I cleared my throat and, with John translating, explained that my food was nearly finished and that we would therefore not be able to have dinner guests any more. My statement didn’t seem to elicit much interest and the general conversation – we were talking about the different colours of cattle various patriclans were required to keep – quickly resumed. I doubted we’d made our point adequately.

Early the next morning, I was woken by the sound of a bleating goat. I stuck my head out of my tent and saw that someone had tied the creature to a tree at the edge of my camp. Then Vengape, whom I had particularly befriended, arrived with a large sack. She emptied it into the back of my truck – a pile of fresh green mealies for roasting on the fire. Before I had finished thanking her, a man who had been at dinner the night before walked into camp carrying a large shoulder of goat for me, with a smaller piece of meat, which was, he said, for my dog. He hung both in a tree near the living goat and drifted off. Then Kata, Vengape’s sister, appeared with a large watermelon in her arms. She laid it next to the mealies and told me through John, who had now got up, that one of the children would be bringing me some honey but that she needed a container to put it in. I went to get a jar, and grabbed my last packet of biscuits to give to Kata as I knew she loved them.

She took the packet but gave me a long look.

“What?” I asked, not needing to be translated.

Kata heaved a sigh, and motioned me to join her at my fire on which John had placed the kettle for our first tea of the day.

“Why,” she asked me, “do you always make yourself high?”

I struggled to understand although she, John and Vengape, who was still with us, seemed clear about what was being said.

Eventually, the penny started dropping.

What Kata meant was that by giving her a present back each time she “gifted” me, I was keeping myself in a superior position and never allowing her to be the dominant gift-giver.

Himba women lubricate their social relations by giving gifts to one another. The aim is to try to be the last one to gift someone and therefore to whom a gift is owed. So when something comes along that you really want – such as a new supply of the red ochre in daily use by women – you are in a strong position to ask for some. If you’re always in other people’s debt, you risk others asking for things you’d rather not give them but which local etiquette requires you to hand over. This concept of reciprocal gifting is well entrenched in many societies. Those who have the skill to keep others in their debt are admired. But to be in the game, you have to play it, which means taking as well as giving. I was effectively excluding myself from this community by always being the last giver.

Kata had been observing me for two weeks and was becoming tired of my gauche manners. The packet of biscuits was the last straw.

As we talked that morning, possibly one of the most insightful sessions I’d had in spite of my copious notes to date, I realised that for all my academic pretensions about laying out one’s world view as the filter through which one does research, the most pernicious biases are the ones you don’t know you have.

I carried an unexamined Eurocentric assumption that relatively speaking I was wealthier than the people here. After all, I had a 4×4 vehicle, a share in a house back in Cape Town, some money and many modern material goods. The people, however, who had learnt that my family had no cattle, goats or sheep, saw me as relatively poor by their terms. The goat brought to my camp was to be the start of a small herd I would accumulate during my years in the north-west. My guests were not eating my food because they needed to – but because they were enjoying the social occasion, the novelty of the different foods I served and they thought I needed the company.

As soon as I mentioned that my food was running out, people automatically started sharing some of theirs with me. They were glad to have an opportunity to do so, which meant a more balanced relationship between us.

*****

Some years after my research ended, my thesis was produced and like most other PhDs, its main use was to fill space in a few academic libraries. But I stayed on in Namibia, wanting to give back some of what I’d gained. Community-based conservation work in the north-west and later the north-east of Namibia, aimed at linking development, democracy and conservation kept me in touch, from time to time, with the Himba families I lived with.

More than a decade after Kata’s lesson about taking as well as giving, she and her husband Wapenga appeared at the door of our NGO’s Windhoek office. Mostly, I worked in the field so it was just luck that I happened to be in town. Over tea and after an exchange of news, Kata explained the serious health reason that had caused the couple to hike to the capital, 1,200 kilometres from Onyuva where she lived. She needed help and it didn’t cross her mind that she wouldn’t get it from me.

That afternoon I took her to a doctor and the next morning she was admitted to hospital for a serious operation. She recovered well and after a month in town, she and Wapenga returned to the north-west. Before she left she took both my hands in hers and looked into my eyes. “No biscuits to give me?” I asked. We both laughed: no more words were necessary. This time it had been my turn to give, paying for their stay in the capital, and Kata’s turn to take. But, we both knew, the gifting wheel would turn and at some time in the future when I was up north, in her area, she would be the giver. A sheep or goat would be slaughtered, and there would be some serious meat feasting. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider