Sci-Tech

Bad Sex – The soft heart of the South African male

It’s the kind of book you read aloud to your girlfriend to help her understand men. Which, if that’s all it was, would be good enough. But Leon de Kock’s first novel Bad Sex is also a finely wrought exploration of lower middle class white South Africa in the apartheid days, a ride through Joburg’s “rof” southern suburbs when the fist ruled and sensitive boys were “meat”. By KEVIN BLOOM.

There’s an image to be found on a certain social media network that serves, perhaps, as summary and symbol for the opening conceit of Leon de Kock’s new novel Bad Sex. The image is rendered in the pictogram form commonly associated with public washrooms, except here the genders appear in one frame together, with the male on all fours and the female – who’s holding his leash – standing upright behind. “Chicks rule,” says the caption. “Boys make good pets.”

We meet Samuel L. Baptista, De Kock’s protagonist, shortly after he has freed himself from just such a position. He is reclining on a rectangular black leather sofa, telling his therapist about his ex-girlfriend, a stunning and wealthy CEO who also happened to be his boss. “I didn’t get to have bad moods because that would crack her mood,” he complains. “She took up all the mood space.”

Not, one might think, the sort of novel to get past the strictures of the MA creative writing workshop – a forum with which De Kock, a respected poet, academic and translator, is intimately familiar. First off, as he well knows, there’s that therapist thing. It’s a device used frequently by amateurs, and because of its obviousness, it’s nigh impossible to pull off. Then there’s the political incorrectness of it all, the unapologetic and downright hazardous plea for male equality at home and at work. Then there’s the awkward matter of the title itself.

And so Bad Sex, in its successful flouting of these rules, is all the more remarkable. What we have in the character of Sammy, in this “Mayfair boykie who made good and got a decent university education,” is an authentic insight into the psyche of the South African male reared in a world of brekers and boxing and booze. A world where men have names like “Eggs” and George “Screwdriver” Zackey and Harry Barbarees. A world where one of Sammy’s boyhood idols, a former boxing champ who drives a Jag XJ6 and lives the “loose life,” instructs him: “When you make it like this it feels like a brick, so when you actually see someone right with a fist like this, he stays down.”

How does a man with such an upbringing find and sustain love? This is De Kock’s question, and it is by all accounts a good one. The mature Sammy, in his own words (to his therapist Anna), is “talking about the real stuff here, the everyday politics of people and the power they hold over each other… the way they take each other in, starting with love and proceeding slowly to surveillance.” For importantly, when Sammy was young, the male defensive stance never seemed a match for the subtle aggression of the female. It was, he informs Anna, recalling his father’s nightly retreats to the gym in the garage, “a sweat-drenched, futile response.” And if surveillance is the state that ultimately follows romance, if young Sammy’s Mayfair role models are the only archetype – violent, lecherous, uncouth – then muscles, as a currency, always lose against “the superior coinage of mockery, gossip and laughter.”

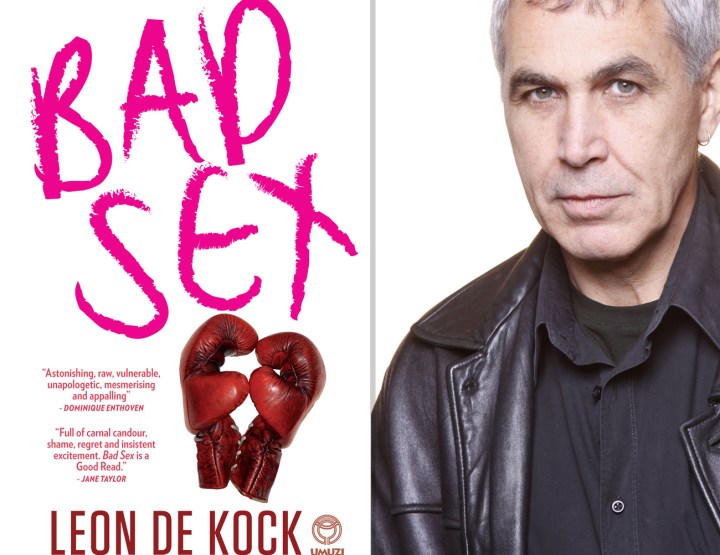

Of course, because little Sammy was undefeated in nineteen bouts as a pinweight, because boxing is the central metaphor of Bad Sex – as highlighted by the gloves motif on the front and back covers – big Sammy fights back. It’s an ancient narrative, the war of the sexes as told against the backdrop of Joburg’s rof southern suburbs. The continuous circulation of the story from Sammy’s past and back again to his girlfriend-less present builds tension and empathy; we want the protagonist to find a solution, which is why Bad Sex can feel at times like genre lit. It’s only when pre-teen Sammy has to forego his dreams of boxing stardom, and instead make weekly visits to Dr Avian for the treatment of his emergent epilepsy, that De Kock exposes the depths.

Sammy, to his numb and passive horror, is fondled by the good doctor – the catch is that he can’t excise a secret part of himself that actually likes it, and so he becomes after a while a willing participant in the exchange. For such behaviour, Sammy knows, for committing the cardinal Mayfair sin of being a “moffie”, his brother Nev and just about every other “ou” on the streets would moer him into yesterday.

Here, then, is where the “bad” in Bad Sex comes from. As a university student, Sammy suppresses his homosexuality and learns how to have sex with women, but the joys of the act still feel for his adult self like “wrongdoing”. He craves the “best kind of bad sex,” the kind where “you do it for the burn, the shock, the violation, almost…”

Given this, the reader asks, does Sammy ultimately deserve redemption? The question is moot. In passages often redolent of the energy and tragicomedy of Phillip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, De Kock has articulated the vulnerabilities of the hardboiled South African male. Bad Sex, as a consequence, is nothing short of revelatory. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider